How Environmental Psychology Can Help You Work Better From Home

Interview with Dr. Sally Augustin, environmental psychologist and principal at Design With Science

Where we are influences how we feel and think. Nobody feels the same in a windowless cubicle as they do when hiking through the wilderness.

However, it can be spooky to hear just how much our environment affects our behavior. Can some evil scientist really control our minds by using cool lighting, hard office chairs and gentle ocean noises?

While the answer is probably no, we could still benefit from knowing more about how design choices influence our psychology. Especially now that many of us are forced by the pandemic to work from home; defenseless before the seductive charms of our televisions and refrigerators.

To gain some insight on what I could do to stay sane and productive while locked down, I donned some suitable clothing and rang up Dr. Sally Augustin, environmental psychologist and the principal at Design With Science. She was kind enough to give me valuable tips on how to take advantage of the lessons of environmental psychology to deal with stress and improve everyday life.

Where you are is always affecting your mind

Alex: I'm very excited, this is the first time I get to speak to an environmental psychologist! What is environmental psychology?

Sally: Environmental psychology is the study of how the things in the world around you influence how you think and behave. Environmental psychologists look at how surface colors influence your creativity and analytical performance; how ceiling height affects social behavior; how people respond to a certain texture against their fingertips, or their feet, for example.

We then add an extra layer of analysis to those aspects of the physical form. We consider how national culture and organizational culture influence people's experiences and expectations in a given space. We consider how different personalities will or should influence design.

Dr. Sally Augustin is a practicing environmental psychologist and the principal at Design With Science. She specializes in integrating science-based insights to develop recommendations for the design of places, objects, and services that support desired cognitive, emotional, and physical experiences.

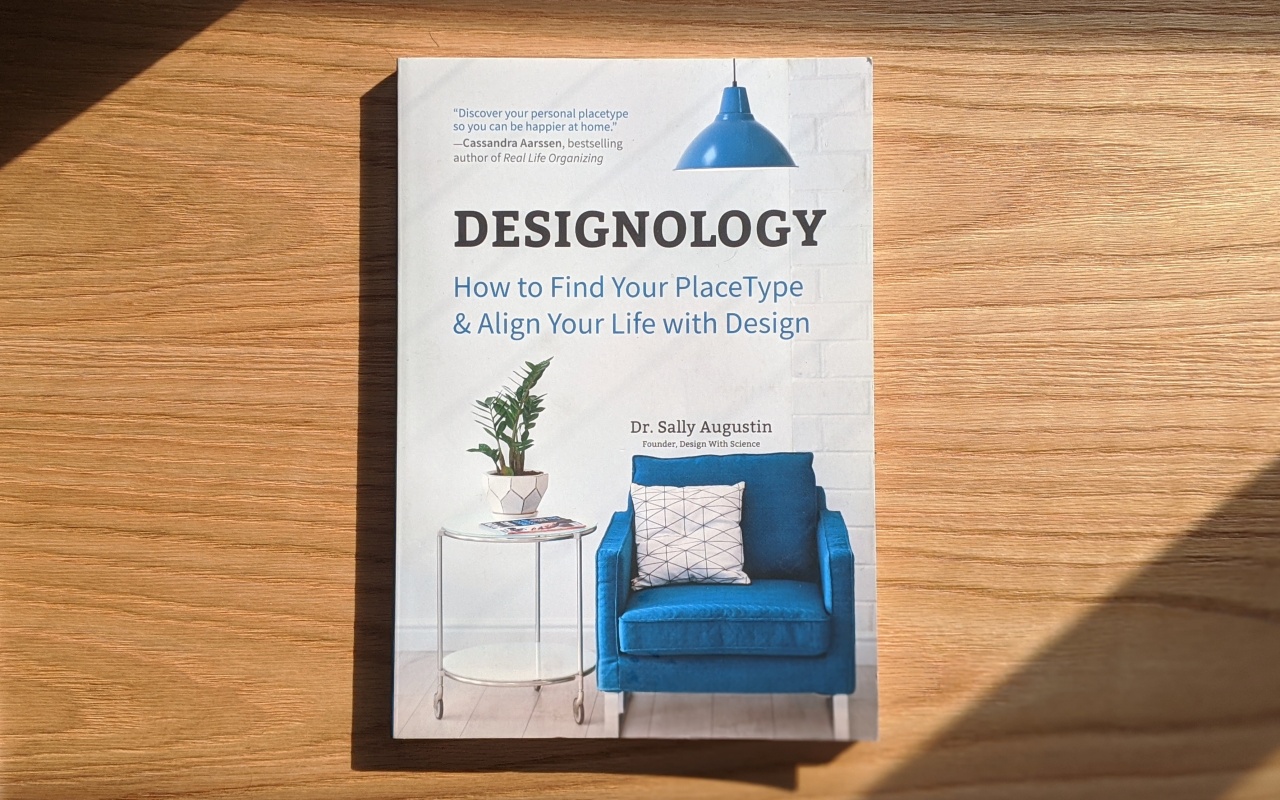

Sally Augustin is a graduate of Wellesley College (BA), Northwestern University (MBA), and Claremont Graduate University (PhD). She holds leadership positions in professional organizations such as the American Psychological Association and the Environmental Design Research Association. Her most recent book is called Designology: How to Find Your PlaceType and Align Your Life with Design .

Alex: Aren't we influenced by pretty much everything in the world around us? I feel like if I have to start paying attention to surfaces and ceiling heights and colors, and look into how they correspond to my culture and personality—it's a bit overwhelming. What would you say are the most important elements we should be paying attention to?

Sally: It's true that there is a lot to consider, but you can develop a sort of hierarchy of which elements should have priority. One way to do so is ask yourself what you plan to do with the space you're designing, which will help you determine which sensory factors to focus on.

Also, many responses are universal. They don't depend on your culture or personality, but simply about what sort of space you're considering.

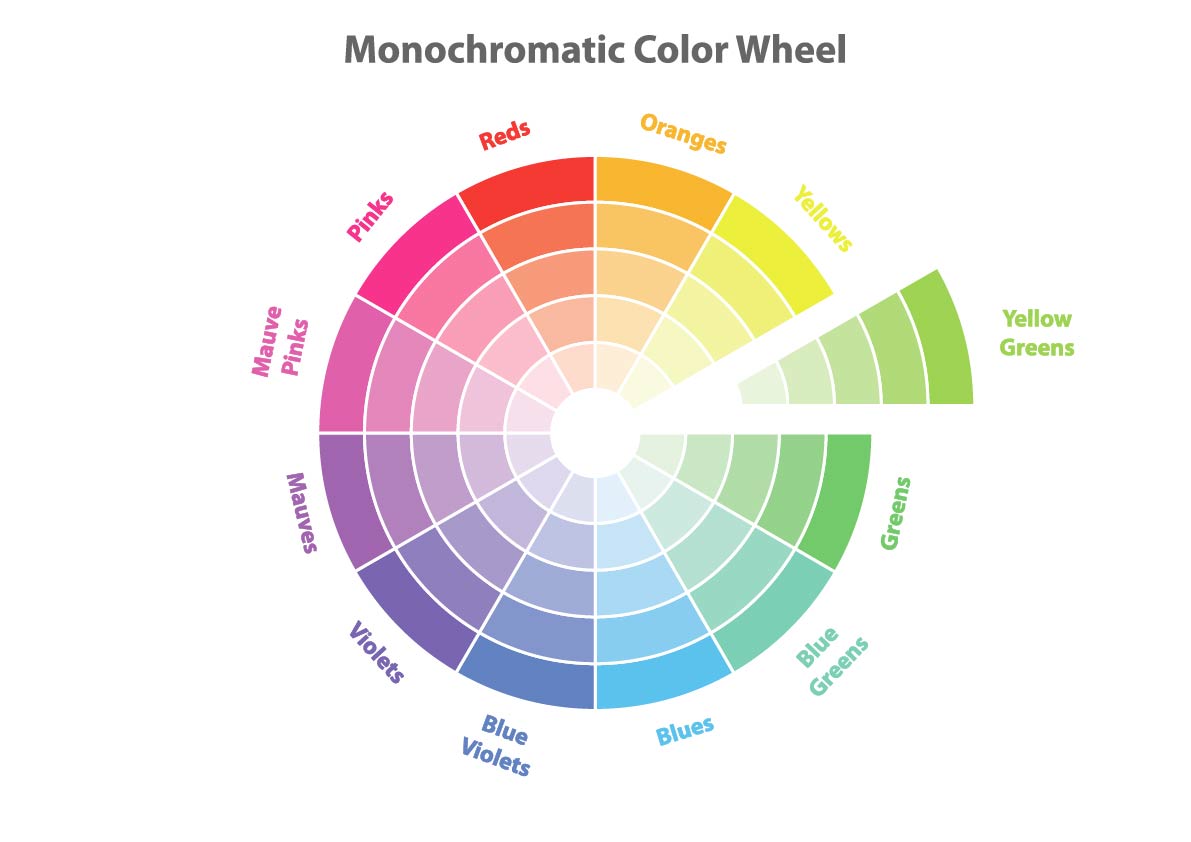

Color is a great example. Each color can be broken down into three attributes: hue, saturation and brightness. Hue is the family of wavelengths that define a color, like blue, green and red.

The color wheel sorts colors by hue and brightness.

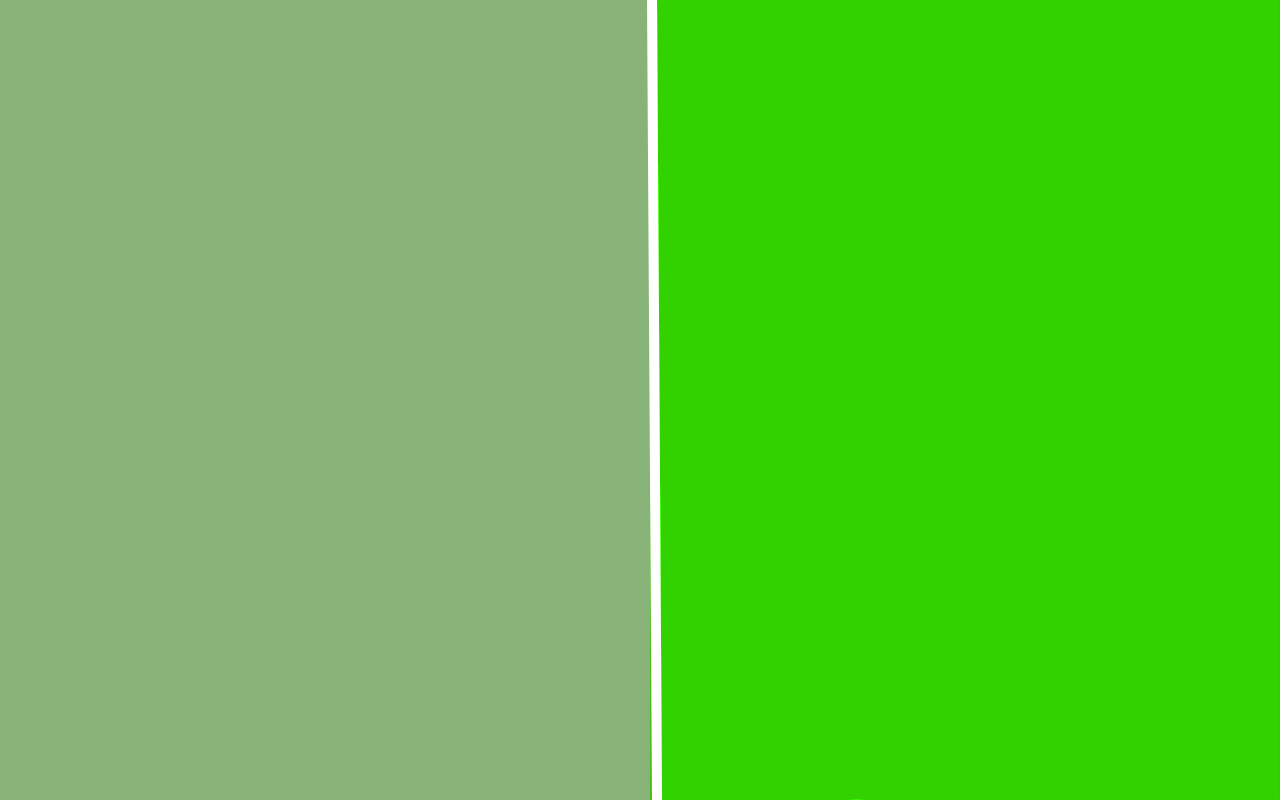

Sally: Saturation is how "corrupted" the color is; in other words a lower saturation color will seem more grayed out than a higher saturation color. For example, sage green is less saturated than Kelly green.

Finally, brightness is exactly what it sounds like: how much white has been mixed into a color.

Low saturation sage green (left) versus high saturation Kelly green (right)

Sally: Universally, brighter colors with lower saturation are more relaxing for us to look at. Take a bucket of the sage green from earlier, dump a bucket of white paint into it and you'd get a relaxing color. The opposite is also true. More saturated colors that are not too bright are more energizing to look at. Kelly green is a good example of that.

This is a constant across cultures and room types, so you should match the color to the way you use a room, whether you want a more relaxing feeling, or something more energizing.

Alex: I've never really thought about color that way, but it makes a lot of sense! Are there any other examples of the universal effects of design?

Sally: Plenty! Another great example is ceiling height. We often feel more creative when in a space with a taller ceiling. That's also why a cathedral or palace will inspire awe in us.

Hall of Mirrors at the Palais de Versailles in Versailles, France

Sally: On the other hand, across the planet, higher ceilings also signal more formal interactions. The reason is that when someone is speaking to you, the sound doesn't just come directly from their mouth to your ears, but also bounces off the ceiling and back down. That bounce takes longer when the ceiling is higher, which makes for a more formal atmosphere.

That's why in the U.S., people will buy these giant McMansions with oversized family rooms and very high ceilings, and then wonder why nobody wants to hang out in them. It's hard to just hang out, have a great time and socialize in a room with a very high ceiling.

Most people find it uncomfortable to hang out and relax in a living area with a high ceiling.

Alex: That also matches up with my personal experience, but I never really thought about it from a psychological standpoint.

Sally: I often think that environmental psychology today is where nutrition was 20 or 30 years ago. Back then, people had some idea that how they ate influenced their health and mood, but most people's understanding wasn't really grounded in science. Now, go out onto the street and ask a random person some very detailed questions about nutrition, and chances are they'll be able to answer! You'll get a very detailed explanation of which supplements they take and why.

Environmental psychology seems very complex because it's new to people, but when you absorb these rules gradually, one by one, they will seem natural. In the beginning there's a lot to keep track of, but it becomes easier over time.

Alex: I find it very appealing that your research impacts everyone, all the time.

Sally: Absolutely. I don't want to turn this into a metaphysical discussion, but if you think about it, we're always somewhere. We're always in a space. Whether it's your office, your home, or a spacecraft headed for Mars, you're somewhere. And that somewhere is affecting you in some way. Design helps us manage that effect.

Each space should serve a specific purpose

Alex: We talked about some universal principles in environmental psychology, but now I'd like to focus specifically on work.

With the ongoing pandemic, a lot of people are working remotely, perhaps for the first time. Even once we overcome the virus, I believe this trend is likely to continue. What do I need to consider when designing my personal home workspace?

Sally: The most important thing is to first think about what you're doing to bring value to your organization. For most of us, we do tasks that require concentration and focus, so we need to create a workplace where people feel calm and relaxed, but not so relaxed that they're falling asleep. Hardly any of us do our best work while snoring. (laugh)

When working from home, there's only so much you can do to really optimize your workspace. If possible, you want to be surrounded with colors that can help you relax, like the sage green with lots of white that we talked about earlier.

More importantly, if your work requires concentration, you want to minimize audio and visual distractions. You want your place to be quiet, but not completely silent—that would be freaky. This is true when working from home or at the office: You want to create a space where you can't hear other people having conversations. Our brains have evolved in a way that we can't help but pay attention to the conversations happening around us, so we have to shield ourselves from that.

I recommend playing nature sounds, but very softly. Those sounds can help keep stress levels in check. Think of the sounds you might hear in a beautiful meadow on a wonderful spring day: a burbling brook, leaves rustling, birds chirping in the distance.

The key word here is gently. You don't want torrential rainfall, no hurricane-class winds, no screaming parrots. Also, you will reap the benefits without these sounds being loud. Think of the nature soundtrack as a subtle addition to your space; not an experience you want to share with your next-door neighbor.

Alex: Nice, I can just download "Sounds of the Peaceful Meadow!" How about lighting?

Sally: Light has a tremendous influence on us. First of all, it's great to sit in natural light—as long as there isn't any glare on your computer screen. Research shows that natural light is directly linked to improved mood and enhanced performance. When we're in a good mood, we're better at solving problems and we get along much better with others. So natural light is great, even if you don't have a view.

When it comes to artificial light, one thing you can do—especially when working from home—is have different color bulbs for different sorts of work. Cooler light makes people more alert, which is great for analytical work. Warmer light is better for creativity and getting along with others. If you're on a call with your boss and things are a bit tense, you probably want to be in a warmly lit space.

A great example of this is Hygge; the Danish way of creating a cozy environment. Hygge uses fire light to create an environment that works well for socializing. When you think about it from an evolutionary perspective, for eons human beings socialized around fires, and our senses have likely evolved to recognize that special link.

Speaking of fire, research also shows that when we touch something warm, even after we put it down, we have warmer feelings about others. We feel more generous and empathetic. It's really interesting just how many links we've been able to find between the physical world and what goes on in our heads!

Warm light, like the light of a fire, can create an environment that works well for socializing.

Alex: That's fascinating! Sadly I don't think I should be lighting fires in my small Tokyo apartment, but I can definitely switch between warm and cool lighting. What else would you recommend?

Sally: Earlier I talked about limiting audio distractions, but you should also be careful about visual distractions. You want a place that's relatively clutter free, but not bizarrely, antiseptically clean.

We thrive in places with moderate visual complexity. By that I mean about the same number of colors, shapes and objects (in an orderly arrangement) you would find in a Frank Lloyd Wright residential interior. Looking at how those kinds of interiors are organized will give you an idea of what you're shooting for, whether at home or in an office environment.

An interior with moderate visual complexity.

Sally: You can leave out some things you're working on, maybe a few personalizing items—that vase you got when on a great trip abroad, or that picture of your family—but not much more than that.

The reason moderate visual complexity is ideal for us also goes back to our evolution as a species. We needed to be able to see things we found delicious, as well as things that found us delicious. In either case, we needed to see it before it saw us. Scanning our environment is more difficult when there's a lot of stuff around, which is why clutter makes us tense.

Alex: Keeping the mess to a minimum when working from home is my biggest daily struggle.

I'm particularly fascinated by how all your advice ties back to our evolution as a species! How about our relationship with nature?

Sally: If you're doing work that requires focus or creativity, having a green leafy plant around is great. Looking at such a plant helps us refresh when we feel mentally exhausted. They've also directly been linked to enhanced creativity.

We've also found that wood with visible grain can help with stress. I recommend a desktop made out of real—or at least real-looking—wood grain. The important thing is for the grain to be visible and have irregular patterns; imitation is fine as long as it doesn't have any unnatural patterns.

Looking at wood with visible grain can help reduce stress.

Sally: You can also refresh by looking at relatively realistic paintings of nature scenes. A meadow it looks like you could step into, with some trees around. You could also have a photograph of nature.

Gently moving water also creates a sound we find refreshing, so you could add a small fountain to your desk. That way you don't need to buy an acoustic nature track; instead you can use that tiny desk fountain everyone got as a gift from their aunt in the 90s!

A feng shui portable fountain.

Sally: Humans have evolved to move around, so having some flexibility in your physical environment is really important. You can alternate between sitting and standing, or change your sitting position to face different directions. Adding that variety can be great.

Design has its limits

Alex: Speaking of distractions, one of the biggest challenges many of us face when working from home is the temptation to do what we usually do when not working.

If I'm near the TV, I may be reminded how much I want to keep watching that show from last night. If I'm sitting close to my fridge, it becomes really tempting to just reach in and grab something. Is there a way design can shield me from these distractions?

Sally: Putting things out of view is great; if you can't see something, you may eventually not think about it. That being said, usually problems around eating too much or turning on the TV are a symptom of being bored, stressed or unable to focus. You should deal with those first.

At the end of the day, there's only so much your physical environment can do. If someone next door starts to cook a delicious meal and your window's open, you're a goner. Regardless of the color you paint your walls.

Dr. Sally Augustin's 2019 book, Designology: How to Find Your PlaceType and Align Your Life with Design

Don't go full remote just yet

Alex: The last thing I'd like to know is, even once the pandemic is over, more and more people may decide that working from home is good for them. What is your take on working from home versus going to the office? Are there certain types of work for which home is more suitable?

Sally: This is going to sound like common sense, but honestly it really depends on how much interaction with others you require to do your job well. Even for a lot of creative professions, you need honest feedback from others, and there's no substitute to getting that in person.

We're used to thinking that humans only communicate by words and gestures, but that's not true. There are many nonverbal ways in which we signal each other. How close you stand to somebody. Whether you make eye contact when you talk. How you smell. And I'm not talking about sweat; we actually smell differently when we're happy and when we're not.

All sorts of communication channels are blocked when you're not in the same place, so if you need feedback or interaction to do something, you'll need physical proximity with colleagues. Perhaps you can prepare for those interactions by working from home, but that's not a substitute for meeting in person.

Alex: What if I'm doing something mechanical and uncreative, like sorting files or inputting data?

Sally: Interestingly, research shows it's better to do those kinds of tasks with people around you. The reason is that when you're doing something simple or well-practiced alone, you tend to zone out, which in turn degrades your performance dramatically. That little jolt of energy you get from other people can keep you from daydreaming.

Alex: A lot of people nowadays are touting how amazing video conference technology has become. But for you, that's still not a viable substitute for coming into the office?

Sally: There are so many problems with video chat that we don't really have time to get into, but one example is eye contact. Everyone knows how important eye contact is in conversations, yet it's not something you can do when video chatting. I mean, you can stare into your webcam, but that's probably just going to look a bit disturbing.

Our evolutionary history dictates that you simply can't get to know people unless you physically spend some time with them. Even as technology evolves, the complexity of physical interactions impedes what we will ever be able to do with phone or even video communication.

Don't get me wrong, it's great that we have all of these tools at our disposal—otherwise today's economy would probably collapse. But it's a stopgap. We're doing our best to make it work now because we're in a temporary crisis. I feel confident that when people are allowed to go to work again, overall, they won't try as hard with all this electronic equipment—they'll try to talk to each other face-to-face.

Article by Alex Steullet. Edited by Mina Samejima. Featured image by Dan Takahashi. Sally Augustin's photo courtesy of Sally Augustin.

Writer

Alex Steullet

Alex is the editor in chief of Kintopia and part of the corporate branding department at Cybozu. He holds an LLM in Human Rights Law from the University of Nottingham and previously worked for the Swiss government.

Photographer

Dan Takahashi

Dan is an editor and photographer for Kintopia's Japanese twin website Cybozu-shiki. He is the most recent member to join the corporate branding department at Cybozu.