Foreign workers key to maintaining Japan's economic competitiveness

This is the first article in our series "Diversity and the future of the Japanese workplace." Together with The Japan Times, we examine the changing workplace environment and what the future of work may look like as companies embrace diversity, internationalize their human resources and adapt to new working conditions.

It only takes a few minutes of conversation with 45-year old entrepreneur and CEO Yohei Shibasaki to realize he has a far more global outlook on society than your average Japanese businessperson. Having previously worked abroad for Sony, Shibasaki would regularly interact with top talent from major firms around the world. Over time, his understanding of the differences between Japanese workers and their overseas counterparts grew significantly. He was particularly surprised to find that while Japanese workers demonstrated great discipline and a firm work ethic, they often lagged behind in specialized knowledge.

"Wherever I went, I was astonished by the level of specialization among foreign workers," Shibasaki recalled. "We didn't have as many specialists at Sony, but were nevertheless able to maintain a strong market position for decades thanks to the collective dedication of our workforce. I started imagining the possibilities that could arise if Japanese companies joined forces with specialists from around the world."

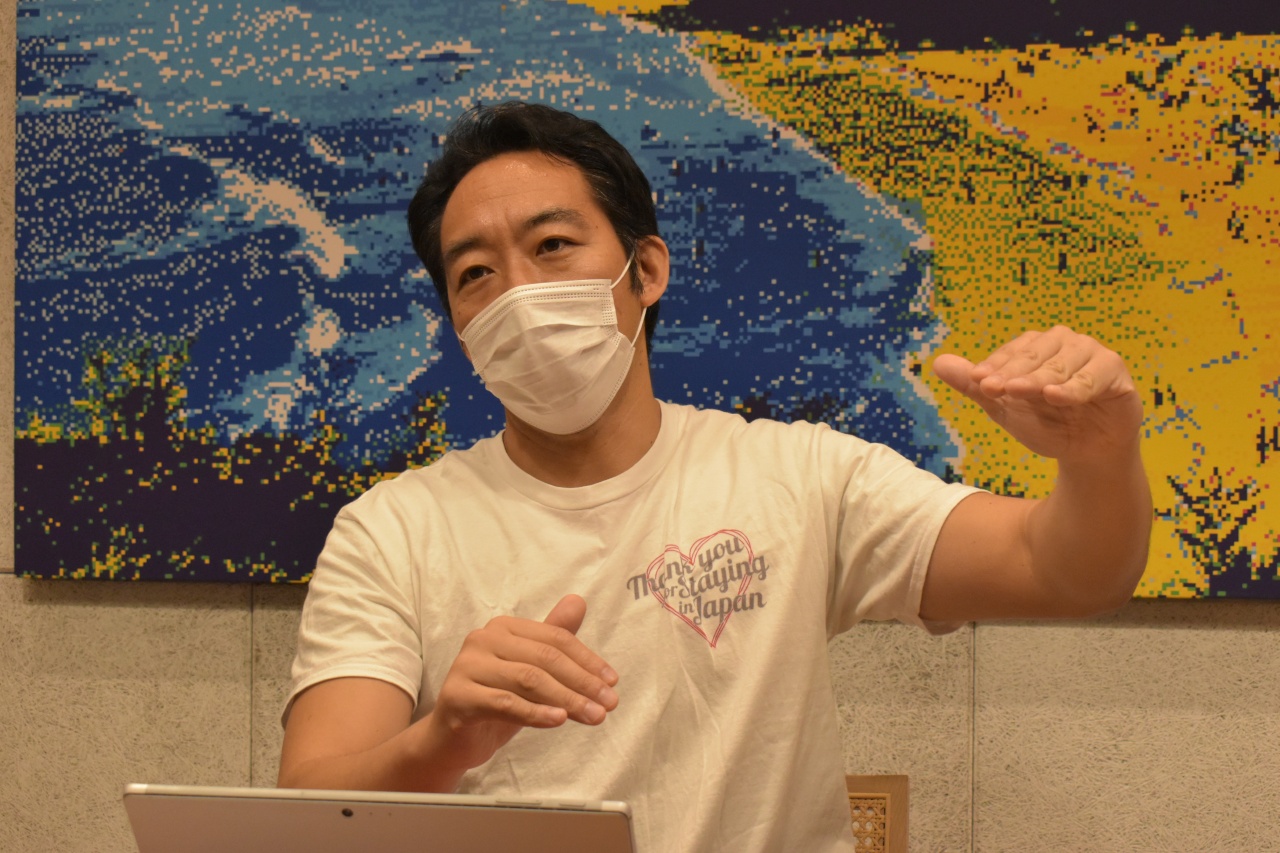

Shibasaki has since become the CEO of Fourth Valley Concierge Corp., a firm that matches Japanese firms with workers from overseas. He is now in a prime position to witness the international collaboration he envisioned gradually become a reality. "Recently, we have been seeing immigration reforms and an increase in international students finding work in Japan after graduation," he said. "The professional landscape for foreign nationals is changing."

Yohei Shibasaki's Fourth Valley Concierge Corp. matches Japanese firms with workers from overseas. MARIKO SHIMADA

Looming labor shortage

Due to Japan's aging population, the government estimates a shortage of 1.3 million workers over the next four years. Japan will have no choice but to increase the influx of foreign labor if the country is to maintain its global economic position. As a result, the government is easing immigration restrictions in a bid to attract more talent.

Shibasaki sees this paradigm shift as an opportunity to examine the pros and cons of working in Japan, as well as the economic and societal impacts of a more diverse workforce. He believes that by embracing this new workforce, the country can continue to play to its strengths while utilizing overseas talent to address its shortcomings.

As an example, he points to Japan's national rugby team. "Japan is completely enthralled by the team, of which almost half the players are non-Japanese," he remarked. "The team's success and the way it has been embraced by society prove that when united, Japanese and non-Japanese can come together and accomplish great things."

Japan's often overlooked advantage

There is also a more pragmatic reason for Japan to welcome a diverse workforce: economic competitiveness. "If we were to compete with regional rivals like China while relying only on domestic talent, we would surely lose. However, I have no doubt that if Japan were to supplement its strength with talent from India, Nepal and Vietnam, it would bolster its economic foothold internationally."

Japan already enjoys an often overlooked advantage over some of its regional competitors: the relative ease with which people from overseas can acquire a work visa. International students enrolled in Japanese universities and vocational schools can obtain one upon graduation by simply finding an employer to sponsor them. Since 2013, the number of international students who have thus changed their status from a student to a work visa has more than doubled. This is in stark contrast to the U.S., where stringent visa requirements often force international students to return to their home countries as soon as they complete their education. In fact, Japan is one of the only developed countries to allow international students to qualify for white-collar work visas immediately upon graduation, which Shibasaki sees as a key advantage for attracting overseas talent.

Non-Japanese without a university degree also have the option to first come as students at a Japanese language school. After learning the language, they can enroll in a vocational school, after which they can find work in their field.

Students are allowed under their visa to work part-time up to 28 hours per week—a provision from which many people from countries with lower average wages than Japan can greatly benefit. Shibasaki notes that a large percentage of students from countries like Nepal, Indonesia and the Philippines take advantage of this right to work part time to send a portion of their wages to their families back home.

Finding the right talent

While wage incentives are appealing to workers from countries with a comparatively lower average wage, the same cannot be said for professionals from most Western countries. Shibasaki remarked that standard salaries for white-collar positions in information technology and other sectors are much lower in Japan than for instance in the U.S. and Europe. Skilled professionals from China are also less likely to consider Japan due to increasingly attractive career prospects in the burgeoning metropolitan centers of Beijing and Shanghai.

According to Shibasaki, Japan's inability to offer competitive wages means the country is not well placed to attract Western workers. Instead, it should look toward other regions to find the talent it needs to bolster its industry and fuel its economic growth.

Japanese management style

Wages are not the only consideration for foreign workers contemplating working in Japan. For example, advancement in Japanese firms is traditionally based on nenkōjoretsu—a seniority system emphasizing age and duration of employment over competence. Ambitious workers who want to quickly climb the corporate ladder will be frustrated by the reality that it may take longer to advance than it would in other countries.

Yohei Shibasaki, CEO of Fourth Valley Concierge Corp., talks about foreign workers in Japan during an interview in his office. MARIKO SHIMADA

"I'm not opposed to nenkōjoretsu, but because of it, there is a lack of young professionals with managerial experience," Shibasaki said. "You would be hard pressed to find anyone in their early 30s with 100 people working under them in Japan's top 100 firms. This differs drastically from the U.S. for example, where high-performing employees can reach important managerial positions in a short period of time."

In lieu of performance-based advancement systems—where a slump in performance can lead to employees having their salaries cut or getting fired—Japanese firms offer stability. Employees generally benefit from knowing that their job is safe and their salary will remain stable.

"There's a common perception that all foreign workers prefer Western-style performance-based advancement," noted Shibasaki. "While this may be the case for top professionals from Europe and the U.S., when it comes to talent from developing countries in Southeast Asia—those who have a financial incentive to come to Japan—the employment stability they can enjoy at Japanese firms is often preferable."

That being said, not all Japanese firms embrace these rigid seniority systems. A growing community of IT firms is incorporating more Western incentive structures, enabling determined workers to perform their way to the top. "This is a great development for foreign workers because they now have options," noted Shibasaki. "They can choose to work at larger firms with a long-standing culture of stable lifetime employment, or at smaller firms where everything comes down to performance."

Entering a market rather than a position

Another perk for overseas white-collar workers in Japan is the flexibility of their work visas. While workers in countries like the U.S. have their visas tied to their employer—meaning their work permit expires upon termination of employment—workers in Japan can change jobs at any time as long as the content of their new job is permitted under their visa status.

This benefit has been extended to blue-collar workers through the introduction of the Specified Skilled Worker visa. Shibasaki sees this as a game changer because it mitigates exploitation; an issue that drew great attention in 2016, when grave violations of Japan's Technical Internship Program came to light. Interns participating in this program had been permitted to live in Japan through visas linked to their employer. Since visas would expire upon termination of the internship, interns couldn't quit out of fear of being deported. Many employers took advantage of this situation by withholding wages and engaging in extortionary practices.

Introduced in 2019, the Specified Skilled Worker visa status rectified this power imbalance by allowing unskilled workers to freely change jobs. The new status allows foreign nationals without qualifications to come to Japan and work in an array of industries, including construction, caregiving, accommodation and agriculture. While the introduction of this new status reflects the government's determination to tackle the labor shortages caused by Japan's aging population, it also sheds light on the fact that white-collar workers in Japan have enjoyed preferential treatment for a long time.

Setting standards for language and education

Shibasaki's firm specializes in matching Japanese firms with both blue- and white-collar workers, helping his clients fill positions that would remain unfilled if it weren't for overseas labor. While under the Specified Skilled Worker visa status, a university degree is not necessary for finding employment in Japan, Shibasaki believes it is worthwhile for his firm to focus its efforts on recruiting from universities—namely institutions in Nepal and the Philippines that have restoration and hotel management departments.

"Even for blue-collar positions, it's best for Japan to attract overseas workers who meet a certain standard of education," Shibasaki said. "For example, housekeeping is one of the most popular courses at Filipino universities. If we can attract graduates of these courses to fill positions at Japanese hotels, it's a win-win situation for those graduates and for Japanese society as a whole."

Shibasaki also highlights the importance of language training, given that a certain degree of Japanese language proficiency is essential to assimilate into Japanese society. His firm has established language training centers in the Philippines, Nepal and Vietnam. It dispatches instructors to provide specialized language instruction to students who have received job offers from Japanese firms.

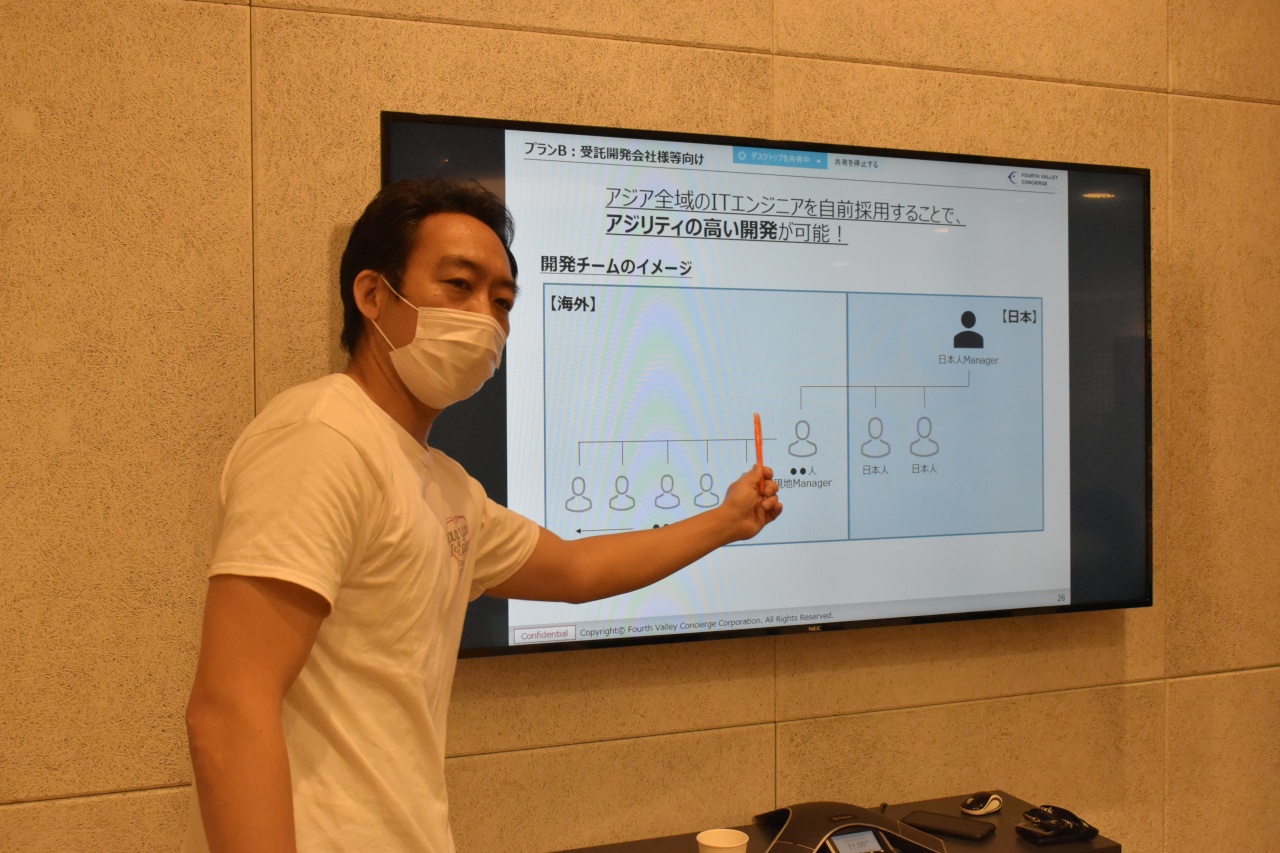

Bringing workers to jobs and jobs to workers

In addition to recent immigration reforms, Shibasaki believes the coronavirus pandemic marks a turning point in how we should think about immigration and foreign labor. As working remotely becomes more widespread in Japan, Shibasaki's firm is looking to implement a remote work model for the recruitment of overseas IT engineers. Under this model, an IT engineer in Delhi would be able to enter an employment agreement directly with a Japanese firm and work remotely from their home country. Since they would no longer need to match Japanese living standards, firms could cut labor costs while simultaneously offering salaries that are competitive in the worker's home country.

Yohei Shibasaki, CEO of Fourth Valley Concierge Corp., says inviting foreign workers and embracing a diverse workforce can strengthen Japan's competitiveness, during an interview on July 15. MARIKO SHIMADA

"Up until now, we've focused on bringing foreign workers to jobs in Japan," concluded Shibasaki. "Now that remote work allows us to transcend national borders, we can turn that model on its head. It's time we consider bringing Japanese jobs to foreign workers."

Whether or not foreign workers will embrace this new model remains to be seen. In the meantime, the tidal shifts expected in Japan's labor demand over the next few years are bound to prompt a response from Japanese firms. Will they welcome greater diversity and come up with creative ways to assimilate new overseas talent, or will they shun foreign labor and focus their resources on the domestic market? One thing we know for sure is that Shibasaki will continue to be a vocal advocate for the former.

Written by Joe Muntal. Edited by Alex Steullet, Ade Lee, Mina Samejima, and The Japan Times. Photographs courtesy of The Japan Times.

Writer

Editor

Alex Steullet

Alex is the editor in chief of Kintopia and part of the corporate branding department at Cybozu. He holds an LLM in Human Rights Law from the University of Nottingham and previously worked for the Swiss government.