Why Is It So Much Easier to Build Trust in War Than in Peace?

Back in the spring of 2018, I was in a foxhole. Or at least that's what it felt like.

I was eight months into this new job as a sales engineer for a small 15-person software startup in San Francisco. When you hear "startup," you may be thinking of one of those unicorn success stories. A small band of savvy engineers catches a lucky break and makes it big by spurring on the next big revolution in tech. My story isn't one of those. Or if it is, I'm still stuck in the first act.

Back then, the way the company was organized was pretty simple. We were two sales engineers (SEs), one for the west coast, one for east. We supported a team of eight account executives (AEs), assisting them in answering prospects' technical questions and building proofs of concept.

It was an exciting time. Our product had been developed in Japan, where it was—and still is—the best-selling groupware product on the market. We had adapted it for U.S. consumers. The whole country was our sandbox; we were wide-eyed, ready to take over.

Then, the other SE quit.

My fuse was on fire

It all happened very quickly. We were already looking to expand at the time, seeking to hire new SEs because the two of us already had too much on our plates. And then there was one.

I've heard stories of what it can be like to go through rough beginnings at a company. But all those stories were told in hindsight, looking back at the hardship with a sense of accomplishment and triumph. When you're in it, it feels completely different. I was working around the clock, seven days a week. It's hard to think of future triumph when you're barely getting through the day.

Tasks were coming in from every side. Everyone needed a piece of my time, even though I was completely out of stock. Missing a beat meant missing a prospect, and missing a prospect typically meant losing them forever. Yet the tasks kept on coming. Some of my tasks were redistributed to the AEs, but it still wasn't enough. With the stress and fatigue piling up, things got out of hand. I could feel the fuse burning at both ends. It was only a short matter of time before I was all burned out.

Luckily, my boss knew what to do. He'd been there before, and he knew instinctively what it meant to display strong positive leadership. He kept me going and taught me a lesson I'll never forget.

I found trust in a hopeless place

I consider weekends to be sacred. They're a time for family, friends, and recharging our mental and physical selves before another week on the grind. Ever since my very beginnings in the professional world, I made it a personal motto to never bother others on weekends.

But back then, I felt like I no longer had a choice. There was no way for me to relax or recharge. It felt like my mind was constantly being bombarded with the mountain of tasks I'd have to get back to on Monday. Even when I wasn't working, the fuse was still burning.

I saw no other choice but to break my own golden rule. My colleague gave one-week notice on a Friday. I needed to get started right away because within a week, I would begin to take the US East Coast in addition to being swamped with work from the US West Coast. I called up our CEO on Saturday and left him a voice message laying out everything I was dealing with. Fortunately, he called me back that day.

Knowing my boss had my back at a time like that meant the world to me. He took the time away from his wife and kids to help. He listened to me and we came up with a plan together. He was compassionate, always looking for solutions that would be in the interest of everyone. Knowing that I wasn't handling things well, he came back and checked on me throughout the next few weeks. I felt like I was on his mind, that he wouldn't let me drown. Without that support, I wouldn't be working for that same company to this day.

Over the following weeks, things slowly began to improve. A few weeks later we hired another SE to replace the one who'd left. A few months after that, we hired a couple more. The war was over. In hardship, I felt like I'd forged new, lasting bonds with those who had suffered by my side. Things were looking up.

Yet somehow, even in peacetime, things didn't go smoothly.

Under my umbrella

About a year after the incident, I myself became a manager. Long story short, it didn't go great.

I work in IT, a field where people will, on average, change jobs every two years or so. When people come into the job, bonding is more the exception than the rule. At first, every relationship is one of convenience; I don't know how long you'll be here, you don't know when you'll leave.

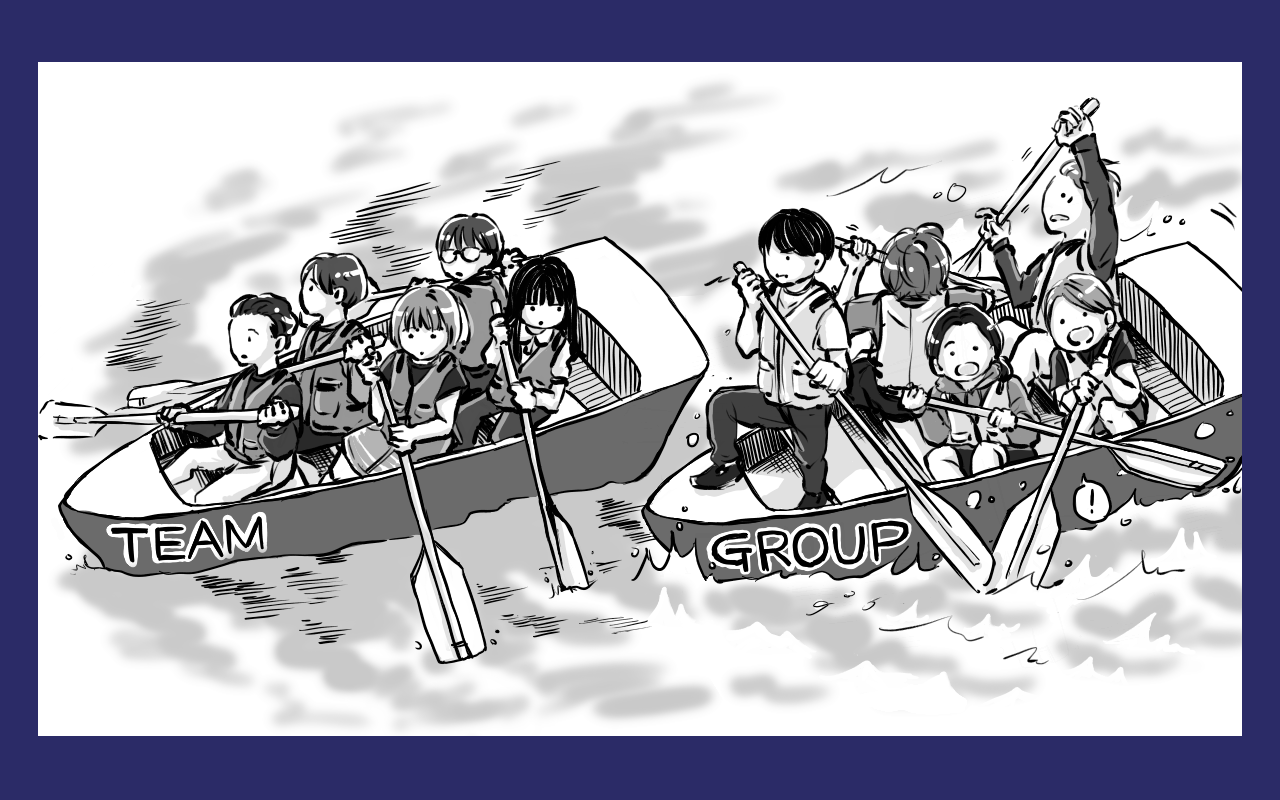

With such an atmosphere, any form of collaboration is superficial at best, artificial at worst. I realized that there is a giant wall between being a group and becoming a team, and as a first-time manager, I slammed into it head first.

When you make a new hire, the first three months are mostly training. Six months in, they're going to want independence and responsibility. Nine months in, they want ownership. It was just around that nine-month mark that my managers called me in for an emergency performance review. My team was unhappy, and they were keen on letting me know why. It was an intervention.

I got an earful. They said I was managing like a tyrant, not consulting them enough. They disagreed with the calls I was making; felt like I was going in the wrong direction. They didn't feel valued or listened to. They complained I wasn't able to help them when they needed it.

At the time, the whole meeting felt like a mutiny. I had spent nine months building my team up, helping them as much as I could. When I was unable to help them, rather than wondering why not and working together to fix it, they saw it as my own individual failure as a manager. When something went right it was because they did it right, and when something went wrong, it was on me.

In hindsight though, it makes sense things played out the way they did. Growing in a company means getting to a point where your manager can no longer solve your problems. On top of that, as a first-time manager I had my own problems to deal with. I had unspoken hopes my team would invest in me the way I was investing in them. Getting everyone to realize we were in the same boat was a critical part of my job, and I failed.

We were all locked in our individualistic bubbles, with expectations we weren't properly communicating. We hadn't been through enough to truly know if we could trust each other, and because of that lack of trust, we weren't able to break down the wall between group and team. Success was personal, failure was on someone else—the opposite of what makes a strong team.

The whole ordeal made me wonder: Why is it that in war time, when everything was collapsing all around me, I was able to forge strong bonds, but in peacetime, when things were going well, none of us trusted each other and things went sour?

Are tough times indispensable for strong teamwork?

My cards don't lie

It's hard for me to say what I could have done to create a cohesive and trusting team back when I was managing for the first time. When I first experienced teamwork in this company, I was under great external stress. But, I wasn't about to drive everyone to their limit only to step in and say, "Hey, I got your back!" My experience with teamwork as a sales engineer didn't resonate with the circumstances I was in as a manager.

However, moving forward, I feel like I have a clearer idea of what the root of the problem is, and perhaps some tips on what other new managers can do to avoid smashing into the same wall I did.

To me, the fact that we struggle so much to be a cohesive team is at least partially the result of a cultural phenomenon, especially here in the United States. As I mentioned earlier, the pace at which we change jobs and the nature of the economy in our sector means we always have to be looking out for ourselves first.

Because of that, a lot of people come into the job with either an opportunistic or downright adversarial stance toward management. They feel like their job is always on the line, so they have to show that they are competent and tough. When employees are driven by the fear of getting fired, they feel like they have more to lose from conflict than their manager, so it's natural for them to harbor grudges and let their concerns fester.

The problem with this attitude is that we know from research that it doesn't lend itself to trust. To trust is to be vulnerable, to get to know each other in a profound way, to be able to set expectations based on empathy and understanding. But how can you be vulnerable if showing your cards means losing the game?

In tough times, we can forge such strong bonds because the rules of the game are different. We all become dependent on each other for our survival as a collective. Revealing ourselves for who we truly are becomes the most rational course of action from an individual perspective. That one weekend back in March 2018, I had to show my boss everything, what I was doing, how I was feeling, where I was lacking—otherwise I would have sunk, and the company would have suffered.

When things aren't as rough, when we're not in survival mode, we need a different approach to teamwork. A much more complex, intricate and sustainable approach. I can't claim to have it all figured out, but here are at least three things to keep in mind when trying to build teamwork in your company.

Let me see your true colors

The first is hiring. Recognize that hiring, when done quickly in a competitive market, is often about facades. Candidates will put up the facade they think is necessary to seem attractive to the company, and vice-versa.

When I started hiring, I was looking mostly for "culture fit." I wanted to know if the hire was aligned with the values of the company. Now, I realize it's more than that. Culture fit means matching the needs and expectations of the team.

Also, culture is only part of the equation. It's just as important to evaluate what a candidate really can and wants to do, and whether or not that matches with what the company actually needs them to do. I've gotten better at understanding that now.

The second is transparency with your team. Meet with your people often; I'd say at least once a week, and go beyond just a rundown of their tasks. One thing in particular that I'd recommend is to ask people outright, "What's not going well for you right now?" Don't stop at "Is everything OK?" to which we're all programmed to reply "Yeah, all good." If you don't know the issues your team is dealing with now, you'll find out when they become big enough to blow up in your face.

My final, most important, but also most difficult piece of advice is to be proactive in creating a culture of empathy. Since vulnerability is the pathway to trust, you have to create an environment where people feel safe, and that means a lot of reinforcement. If a member of your team is saying something that makes them vulnerable, acknowledge it. Let them know that it's OK. That they can speak freely. That we're all here to help, because we'll only succeed together.

If you feel like someone isn't coming forward with their concerns, or never seems to have any concerns in the first place, ask yourself what's keeping them from coming forward, and use that as an opportunity to grow as a manager. Then, talk to them one-on-one. Let them know everybody has concerns, that those concerns are welcome, and speaking out in good faith will never be reprimanded. Show them you're also mindful of your own shortcomings, and they can trust you to be fair with them.

As a young manager you're bound to make mistakes. Only through trial and error will you be able to forge the leadership skills you need to succeed. You'll face the many challenges of building a sustainable teamwork culture that works both in times of peace and times of war. It will be hard. But with these first steps, at least you'll be headed in the right direction.

Oh, and watch out for that wall. You'd be amazed how many of us didn't see it 'til it hit us.

By Nimrod Grinvald. Edited by Alex Steullet and Ade Lee. Illustration by yummi.

Writer

Photographer

yummi

After gratuating from the Nihon University College of Art, yummi began working as a freelance artist. In 2015, she received an honorable mention at the 2nd The Gate competition for her work "Sanpei-sensei No Jikan" (In Her Class), as well as an excellence award at the 69th Tetsuya Chiba competition for “Himitsu No Hanazono-san” (“The Secret Girl”).

Editor

Alex Steullet

Alex is the editor in chief of Kintopia and part of the corporate branding department at Cybozu. He holds an LLM in Human Rights Law from the University of Nottingham and previously worked for the Swiss government.