No Need to Hide: The Benefits of an Open Business Culture

Tired of all the hiding?

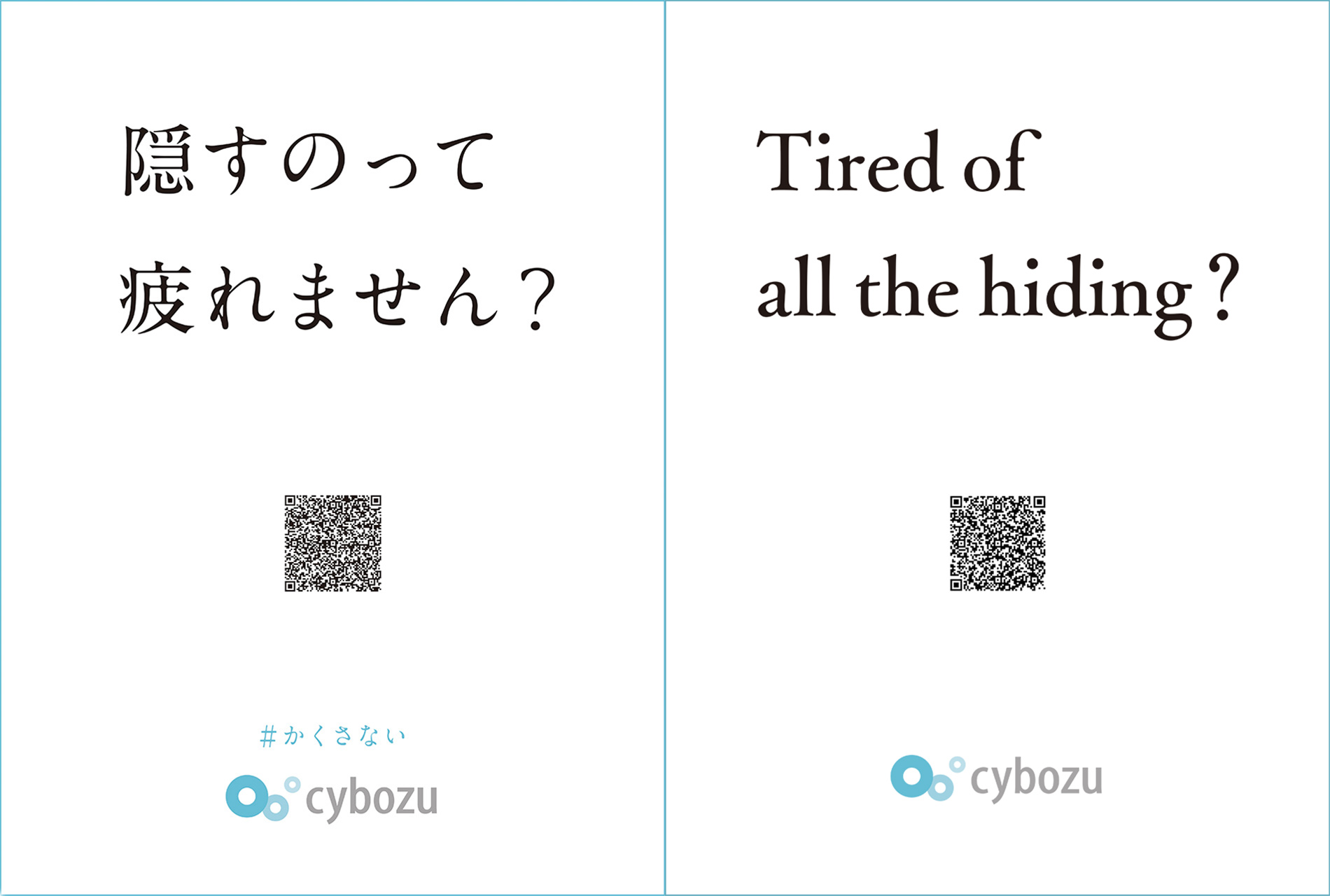

This is the message that appeared in bold print on June 29 in Japan's leading financial newspaper, The Nikkei. It highlights an inescapable truth of modern business culture: The age of open information sharing is upon us.

With the speed at which change happens in the digital era, companies can't remain competitive unless employees are given the optimal conditions to do their jobs. When power-hungry hierarchical structures get in the way, the whole company loses precious time and resources.

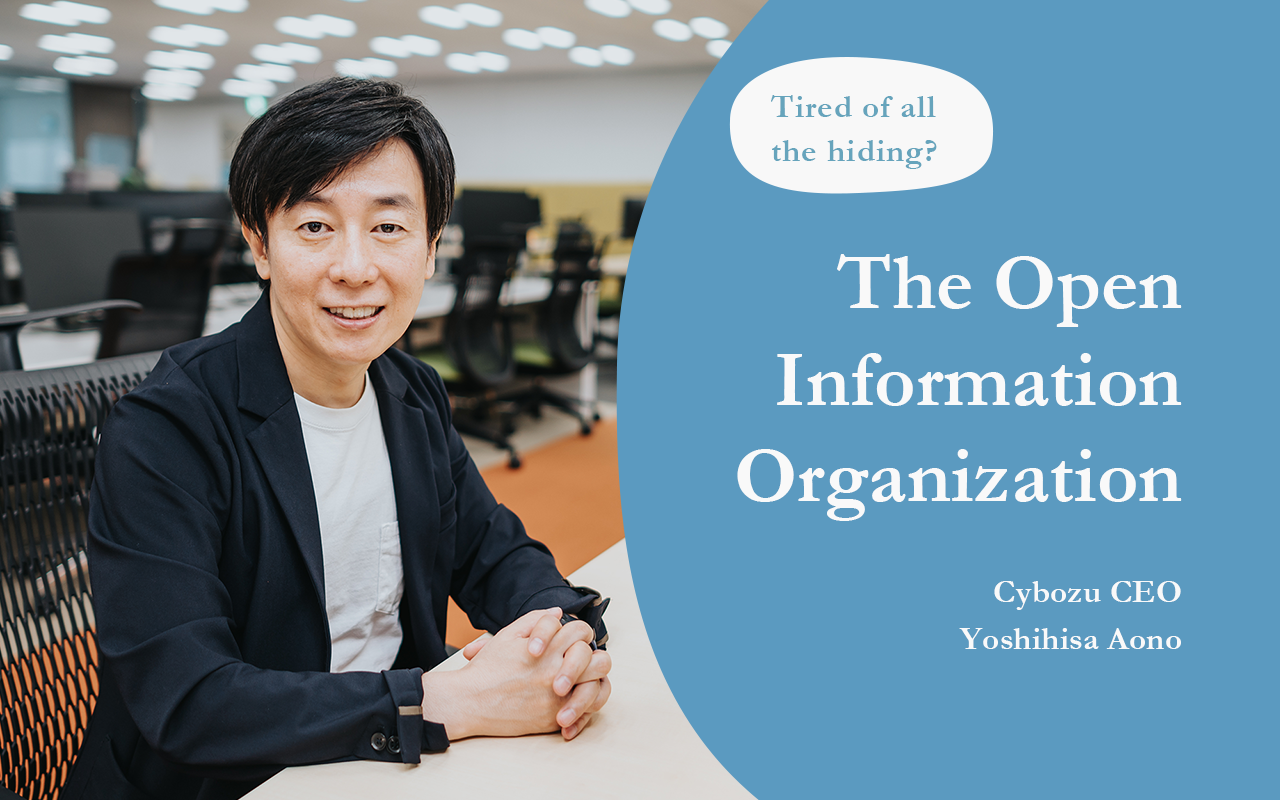

Open information cultures have their own challenges—it's not enough to say, "Let's open it all up!" and see what happens. To learn about the importance of information sharing and how to transition toward a more open culture, we spoke to information-sharing advocate and CEO of Japan's leading groupware development firm Cybozu, Yoshihisa Aono.

Openness is worth a try

Editorial: What made you decide to launch the "Tired of all the hiding" campaign?

Aono: We have to do something to help the young people who are having trouble finding their footing in large organizations. We can't ignore what's happening to them.

On June 29, 2021, the "Tired of all the hiding?" campaign appeared in Japanese in leading newspaper The Nikkei. The English version on the right is a translation.

Editorial: How does openly sharing information help young employees?

Aono: A big reason young people are feeling anxiety in the workplace is that they don't even know how much they don't know. That's what happens in a closed information structure.

I suggest we shift toward a more open structure without an information gap, in which most information is openly shared throughout the company. That's where I believe we as a society are headed.

Choosing not to hide information isn't that difficult. Anybody can do it. It's the current attitude within many companies of always wanting to hide that's exhausting.

Yoshihisa Aono is the CEO of Cybozu. After graduating from Osaka University, he joined Matsushita Denkou (currently Panasonic). In August 1997 he co-founded Cybozu, and in April 2005 he was appointed CEO. Yoshihisa spearheaded the company's workstyle reform, as well as its transition toward its cloud-based product Kintone in 2011. He is the author of several books on teamwork and happiness at work.

Editorial: I see, hence the "Tired of all the hiding?"

Aono: Yes. I think the message will have a strong impact on people who unconsciously hide information. It may also shock some business people and leaders.

It's not like most people are hiding things on purpose. We've just gotten so used to concealing information that we don't even realize we're doing it anymore.

Editorial: Some people are hiding things for a reason though, right?

Aono: Of course, which is why we didn't want to antagonize people with an intransigent message like, "Stop all your hiding!"

We believe that if organizations adopt a more open model, their productivity will go up. It's at least worth discussing within your team. The information-sharing tools you need to support an open culture have come a long way—they're cheaper and easier to use than ever. There's a real opportunity here.

Doing away with internal rivalries

Editorial: Why would different parts of the same company hide information from one another?

Aono: In many companies, the culture is to not share.

Before founding Cybozu, I worked for a large Japanese company. We had a research and development division, a business operations unit, a sales division, and so on. Between them, there was an information wall. For example, a rule we had was to never disclose the manufacturing costs to the sales team. We were told that if the sales team knew the costs, they could go out and sell our products at a discounted price, so we were not allowed to disclose that information.

Even though we were supposed to be on the same team, we ended up having to come up with strategies against one another. It just didn't make sense.

Editorial: It sounds like there were clashes between each section's own interests.

Aono: There was a vertical divide. We're supposed to be a team that works together to provide a great service to the customer, but when walls are put up we become less collaborative and adopt more of an us-versus-them relationship.

We could eliminate a great deal of mental exhaustion by doing away with such rivalries. We would be much better served by instead adopting a mindset of, "Let's work as efficiently as we can, get our work done and go home."

Then there's the added issue of people who get annoyed when communication doesn't go through them. They're the kind of people who get upset and yell, "I didn't hear about this!" or "This should have gone through me first!" How is that way of thinking helping anyone?

Editorial: It becomes a corporate ritual.

Aono: A ritual that's all about feelings and ego rather than logic or reasoning. Imagine all the time we're wasting by accommodating those demands!

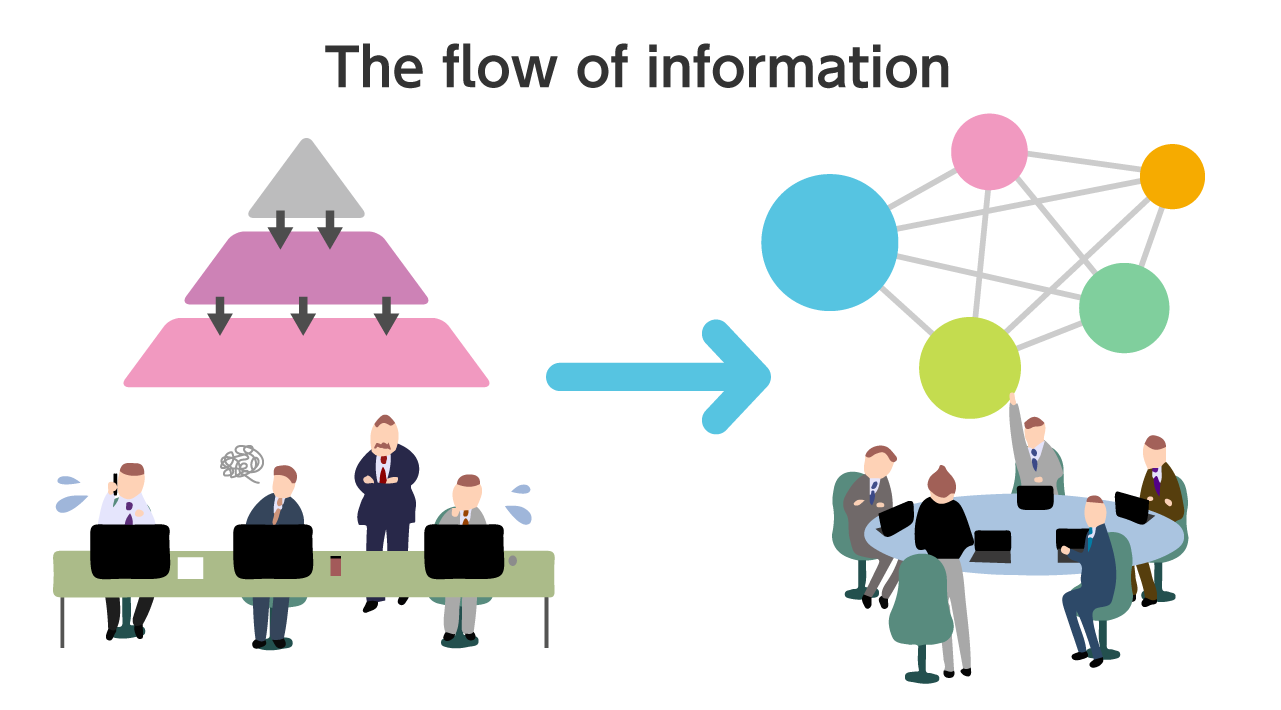

In structures where some stakeholders wield authority over others, all information has to flow through the top of the organization. That causes bottlenecks which become a huge liability for companies with such hierarchical models.

Disarming information hoarders

Aono: Why are we so inclined to hide things when we don't have to? I believe that if we're able to share information more freely, a world of full-on collaboration awaits.

Editorial: It sounds like we've gotten used to there being an information gap.

Aono: The person with authority also ends up controlling all the information, which in turn makes it easier to exercise their authority over people without information. They get to tell people, "Do what I say, or else you won't get the information you need to do your job!"

Aono: By opening up information, you remove the possibility of people abusing their authority to make others do their bidding.

In other words, those who brandish their authority as a weapon find themselves unarmed. It's a complicated issue that takes courage to address, but that you have to deal with if you plan on moving toward an information-sharing company culture.

Editorial: There do seem to be major companies headed in that direction. For instance, we've seen Toyota become afraid their young talent may leave, so they announced they're doing away with their system of putting important information in the hands of a few high-ranking employees.

Aono: Yes, it's the beginning of a trend. However, just because some at the top no longer control all the information doesn't necessarily mean the organization has undergone all necessary changes to become an open culture. There are other factors that need to be looked at in more detail.

It's surprisingly difficult to achieve an organizational structure where there is no information gap.

Company-wide processes

Editorial: Is Cybozu moving toward becoming an organization with no information gap?

Aono: Yes. With the exception of privacy-related information and information that would violate insider trading regulations, the norm is for everything to be openly shared within the company.

Of course, there are still approval and decision-making processes in place within each department. Yet everything from my daily schedule, to the travel costs of individual managers, all the way to the debates and discussions around our 10-year company-wide strategic plan are open to all stakeholders.

Editorial: Could you share an example of what this system has achieved?

Aono: Take our company-wide strategy. Recently, we've been having open brainstorming sessions every Friday.

Editorial: What led you to start having such meetings?

Aono: I wanted to get interested stakeholders together, listen to their opinions, and start making slides and strategic documents while explaining my thought process in real time.

Aono listens to employees' requests in real time while drafting a long-term strategic document.

Aono: For a long time, I would make all the documents myself and receive feedback after my presentations. Now I share the entire process. The reason is that I felt like I was reaching the limit of what I was able to come up with on my own.

Also, I felt a responsibility to hand down my way of thinking. It would be problematic if when I no longer head the company, there's nobody around who can write a strategic document. Now we have employees who can observe and learn from my thought process, and later reproduce it themselves.

Adopting this approach also opens the door for other people to contribute to our strategy. If I try to think of strategic targets myself, I can come up with maybe three per year. If there are 10 of us who understand the process, we can come up with 30.

Editorial: I see; it's like sharing the tricks of your trade with the entire company. Even if they don't end up with the responsibility for developing a long-term strategy themselves, everyone regardless of age and position knows what the thought process is, so they can use a similar process in their own work.

"When I was mostly working from the office, I used to discuss long-term strategies with people from various departments using a large whiteboard in a conference room. These days, the process is completely online. That means my analog skills of writing strategies while talking in front of the whiteboard, which I'd gotten really good at, aren't useful anymore! (laugh)" - Aono

Good communication requires emotion

Editorial: Some people may still have doubts about information sharing, wondering perhaps who would benefit from information being open to everyone. What would you say to those people?

Aono: There are clear benefits. For instance, by openly sharing information, you're more likely to get advice when you need it. Your boss might realize that there's a new and better way of doing things.

Editorial: How would you suggest going about sharing information?

Aono: You have to include your own thoughts and feelings. It's not very interesting to the viewer if all you're sharing is your tasks and schedule. People relate to stories—whether happy or sad, it's the stories you share that move people.

That's something I myself failed to realize in the past.

Aono: I remember one time when I thought I'd come up with an optimal company-wide strategy. I felt like I'd done a perfect analysis of the past year's trends and come up with a logical approach.

Then I shared my strategy, and the reaction I got was, "OK, so what?"

I was shocked! The documents I'd made weren't resonating with anyone. So I decided that without any shame, I was going to share my feelings. I told everyone, "Frankly, I'm frustrated. This year, I want us to win."

When I did that, the response I got was, "That's what we wanted to hear from you!" I was shocked again. What resonated with people wasn't my very logical strategic presentation, but my heartfelt sense of frustration.

Editorial: When you're trying to express something and it's not hitting home, sharing feelings is the key?

Aono: I think so. We see it in our language. In Japanese, 'information' is 情報 (jouhou). It's written with the Chinese characters 情, meaning 'feelings,' and 報, meaning 'report'. That says a lot.

Sharing information together with feelings is perhaps the best way to reach your audience. Even when writing an email or a daily report, it could be a good idea to include a couple of words about how you're feeling.

You can mess up, just don't lie

Aono: When sharing your work, it's also a good idea to include not just your feelings, but also your thought process. We call this Koumeiseidai.

Editorial: You talk about this concept a lot at Cybozu. What is koumeiseidai?

Aono: The term is made up of the four Chinese characters 公明正大, which are meant to encourage people to say what they're thinking publicly (公), clearly (明), honestly (正) and loud (大) enough for all to hear.

When a problem occurs, koumeiseidai is what will determine if people can openly share the reasons for what happened or not.

What's important isn't to openly share all information. It's when you can't share information, you explain to everyone, "Here's the limit to what I can share, and this is why."

Editorial: In connection to koumeiseidai, we often hear you use the expression, "You can mess up, just don't lie."

Aono: That's right. At first, I just wanted people to not lie. The "you can mess up" part came later.

The reason people lie and hide things is because they don't want to face potential consequences. Sometimes when you're honest with someone, they may get mad at you. You don't want that, so you lie.

That's why I add "you can mess up." To remind everyone that we're all human; everyone makes mistakes. It's important for teams and organizations to acknowledge small mistakes and failures. Otherwise there's no way we'll be able to realize true open information sharing.

Editorial: That's true. If you don't let people be open about their mistakes, you risk developing a passive company culture.

Aono: You have people pretending they never do anything wrong, and when they do, they hide. The opportunity to learn from their mistakes is lost.

Sharing with empathy

Editorial: How do you decide which information should be shared and which shouldn't?

Aono: Through discussion. When you begin a conversation, one side has to ask their questions, and the other has to provide answers. At Cybozu, every stakeholder has the responsibility to ask questions and give explanations. It's important for company culture that people not run away from such conversations.

Editorial: What should people pay attention to when having such conversations?

Aono: You have to imagine the other person's perspective.

Editorial: Like imagining how your words are being interpreted when communicating with someone?

Aono: Yes, that's important. You never know for sure how another person will interpret the things you're saying. Assume that you and your interlocutor are different—that everyone you talk to is a bit different, and imagine what it would be like in their position.

It's really hard, but that's how you build an environment in which people have psychological safety. If you have people vociferously arguing with each other, everyone ends up exhausted. I want to create a culture in which people can at least speak and listen to one another normally.

Editorial: The more I listen to how you describe an open culture, the more it feels like sharing information is a skill. How do you get better?

Aono: Start by getting to know the people you're talking to. If you don't know what resonates with them, it will be hard to move them. Knowing your interlocutor is in my opinion a more important skill than your ability to simply convey a message.

"I get asked a lot, 'How do I get as good at making presentations as you are?' The first thing is to know your audience, otherwise you're not going to know the direction in which to take your presentation. You see plenty of presentations where the speaker is very eloquent, but still leaves the entire audience behind. (laugh)" - Aono

Bridging the information gap

Editorial: By sharing information a little bit at a time, it sounds like the goal is to get to a point where there's no longer an information gap in your company. Is that what Cybozu is aiming for?

Aono: Yes. Over the years, Cybozu has gotten rid of most of its information gap. I'd like to keep that process going.

At the same time, it's important to share our knowhow with the rest of society. By simultaneously getting things moving internally and externally, we can slowly transition toward a society without an information gap.

I'm curious how things will be 10 or 20 years from now. I feel like the efforts we're making to realize our vision today could wind up having a broad positive impact for everyone.

Editorial: You want to get rid of the information gap for all of society! Why are you dedicated to enacting social change?

Aono: We can't overlook the hardships our businesspeople are going through. I don't think we'll be able to reform society in one fell swoop, but over 50 or 100 years I think we'll see meaningful change.

I don't want to give up. We've done this in past ad campaigns as well—by first sharing what we've been able to accomplish internally, we hope to sow the seeds of change in other organizations. The idea of an open information culture will take root and one by one, we'll see other companies give change a chance.

It doesn't matter how much time it takes. As long as we are determined to not hide information, we can end up bridging the information gap.

"Within the advertisement, there's the hashtag #かくさない (kakusanai) meaning 'don't hide.' We encourage people who have experienced problems due to the information gap, or who have been forced to waste time on pointless tasks because information wasn't properly shared within their company, to recount their experiences using the hashtag. By seeing what others have experienced with #かくさない, we hope to take the first steps toward building a better society." - Aono

Article by the Cybozu editorial team. Translated by Alex Steullet. Edited be Ade Lee, Mina Samejima and Meg Shimoji. Pictures and graphics by Dan Takahashi. The original Japanese article is available at the link below.

Writer

Alex Steullet

Alex is the editor in chief of Kintopia and part of the corporate branding department at Cybozu. He holds an LLM in Human Rights Law from the University of Nottingham and previously worked for the Swiss government.

Photographer

Dan Takahashi

Dan is an editor and photographer for Kintopia's Japanese twin website Cybozu-shiki. He is the most recent member to join the corporate branding department at Cybozu.