A Blameless Culture Is More Welcoming for Everyone

Interview with associate professor Shinichiro Kumagaya

We all have our differences—whether it's our appearance, personality, hobbies, family structure, or illnesses, no two people are the same. Which begs the question: How do we form organizations in which individuals with such diverse characteristics can collaborate smoothly?

Cybozu founder and CEO Yoshihisa Aono has been working toward developing an organization that operates along the principle of "100 people, 100 workstyles." In order to gain a deeper understanding of what that would entail, he met with Shinichiro Kumagaya, associate professor at the University of Tokyo.

Professor Kumagaya conducts a type of research known as tojisha-kenkyu, which loosely translates to "research that interested persons conduct on themselves." He looks at the mechanisms that allow individuals with a disease or disability to interact and cooperate with those around them. Professor Kumagaya himself has cerebral palsy.

We asked the professor: What kind of company culture would be necessary to create an organization in which all individuals, regardless of disease or disability, could work comfortably and feel that their diversity is embraced?

We are all imperfect people

Shinichiro Kumagaya is a medical doctor and an associate professor at the Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology of the University of Tokyo. He was born in 1977 in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan. As a result of neonatal asphyxia, professor Kumagaya has cerebral palsy. He has been using a wheelchair ever since. After graduating from the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Tokyo, he worked in the pediatrics department at Chiba-Nishi Hospital and in the pediatric cardiology department at Saitama Medical University. He is currently enrolled in a doctoral course at the Graduate School of Medicine and Faculty of Medicine of the University of Tokyo, where he conducts his research. Professor Kumagaya specializes in pediatrics and the tojisha-kenkyu research method.

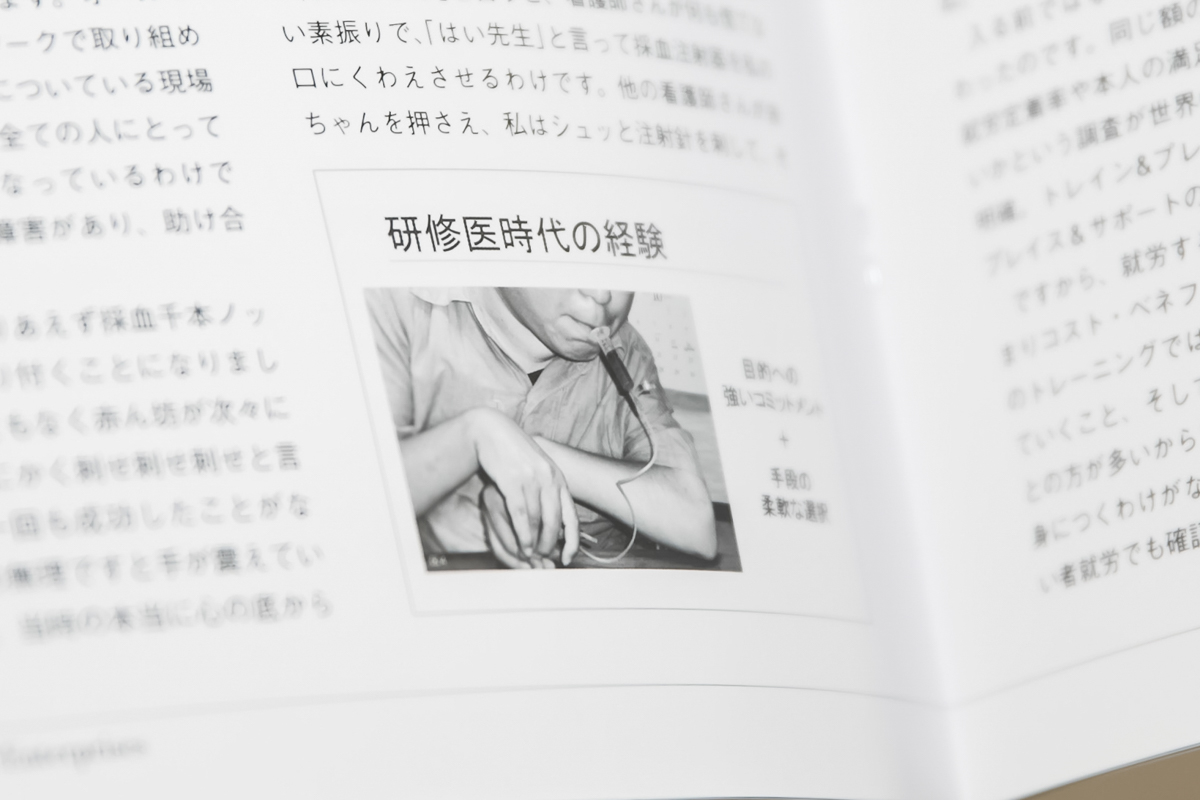

One of the first challenging tasks inexperienced pediatric interns undertake is performing blood draws on infants. We have to insert a hypodermic needle into the thin vein of a thrashing baby, while at the same time feeling pressure from the parents.

It's something that anyone would mess up in the beginning. However, the impact of failure was much greater for me in a wheelchair than it was for other doctors. There were even cases where I would be removed from the procedure at the request of the parents.

As a result, the other medical interns could learn from their mistakes, hone their skills and become independent. I on the other hand would become impatient, mess up more frequently, and fall into a vicious cycle.

As I kept making mistakes, there became this atmosphere of "Let's not let Shinichiro do the procedure."

Yes, the hospital I was assigned to during my second year was extremely busy. I told myself going in that if I couldn't find a way to make myself useful, I might as well quit pediatrics altogether. However, while I was working there, something unexpected happened.

My supervisors and colleagues were all extremely busy. They were keen on me becoming independent as soon as possible so they could have more people in rotation at the hospital.

That environment allowed me to practice what I was bad at, namely blood draws, by repeating the procedure a thousand times. I eventually overcame my weaknesses and after a month, I was even entrusted with being the on-duty medical intern.

Yoshihisa Aono was born in 1971. After graduating from the Information Systems Engineering Division of the School of Engineering of Osaka University, he joined Matsushita Denkou (currently Panasonic). In August 1997 he co-founded Cybozu, and in April 2005 he was appointed CEO. Yoshihisa spearheaded the company's workstyle reform, as well as its transition toward cloud-based products in 2011. He is the author of several books on teamwork and happiness at work.

For example, to do a blood draw I had to hold the syringe with my teeth. In response, the nurses would have to improvise by getting into a particular formation.

Some mistakes are better than none

When I think about people with disabilities finding employment, I often turn toward research on high reliability organizations. These are organizations that cannot allow any mistakes—like hospitals and nuclear power plants. Researching them shows how close we can actually get to a zero-mistake environment.

A surprising conclusion of this research is that the only way to reduce the overall number of mistakes is to allow some mistakes to happen.

If your thinking is "I'm going to attribute the mistake to a culprit, look for that culprit, and demand reparations for their crime," people will naturally become inclined to hide their mistakes. In doing so, both the individual and the organization will lose out on a precious learning opportunity, making them more likely to repeat the mistake.

Mistakes are a valuable source of learning. When a mistake occurs, the important thing is not to look for a culprit, but for everyone to come together, attribute the cause of the mistake to the organization and look into what went wrong.

To each their own way

It seems like one of the hospitals prioritized the end result, whereas the other focused more on process.

Because the second hospital was so busy, they had to focus more on results, which led them to want to help you become independent. On the other hand, the first hospital really wanted you to carry out the procedure the "right way."

Absolutely. To support people with disabilities at the workplace, it's essential to set clear goals while remaining flexible about how to achieve them.

At the first hospital, I read the manual on blood draws time and time again, but it only explained one "right way" to do the procedure. It was replete with instructions that I couldn't possibly follow, leaving me in an impossible situation.

At the second hospital, I began to believe that what ultimately mattered with blood draws was to achieve my goals. As long as blood could be drawn safely and in a short amount of time, a variety of procedures could work. This led me to my unique style of holding the syringe in my mouth.

As long as emphasis is put on achieving the objective, processes can be flexible and modified in ways that wouldn't be possible using a manual written for the average user. Doing so creates a welcoming environment for people with disabilities.

It seems that organizations that value process over objectives are less capable of achieving breakthroughs when confronted with a problem that wasn't covered in the manual.

It's the same in management. Following a general manual won't necessarily lead to correct answers. When doing business, it's far more important to be able to focus on what's necessary in the moment.

We need to expand our research

When it comes to creating a society that works for everyone, I've realized just how important it is to conduct more research on unclear disabilities.

While there are many hardships for people with clear disabilities—such as being excluded more often or getting groaned at when getting on a crowded train—we are spared some of the cost of needing to explain ourselves. Without me having to say a word, society can guess some of the issues I may face and the needs I may have.

However, when it comes to unclear disabilities, such as mental disorders, it can be difficult to understand what makes that person "different." Not just for those around the person, but also for the person themself.

Even when their "difference" is noticed, if the underlying cause is unknown it can be hard to come up with solutions, leading to the perpetuation of difficult situations. Because the disability is unclear, the individual's character will often come under attack. These people become perceived as not working hard enough or lacking willpower.

It's chaos and confusion. The language these people need to express what they're facing isn't well known throughout society, so we don't know how to intervene and make their lives easier.

As a result, it isn't unusual for these individuals to express themselves by engaging in what's often described as "problematic behavior," such as screaming or throwing things. They've reached a situation in which that behavior has become their only means of communicating with others.

Before people with unclear disabilities can advocate for their own needs, it's important for them to gain an understanding of who they are.

Setting ourselves as the research subject and, together with our peers, unraveling the issues that we face; that's the idea at the core of tojisha-kenkyu.

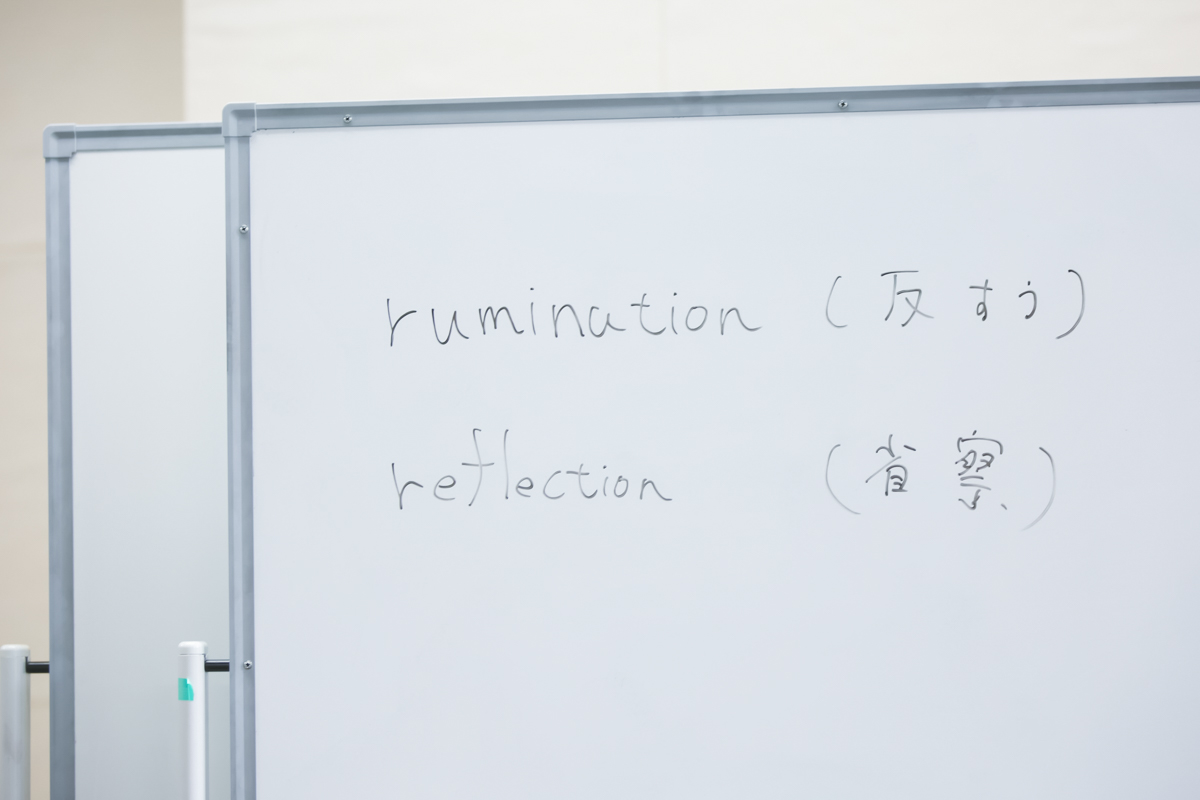

Reflect, don't ruminate

Let's take the example of an individual whose problematic behavior is that they frequently commit criminal activity. There are two ways for this individual to re-examine themselves.

The first is rumination. This basically consists of investigating ourselves and our problematic behavior to the point of blaming ourselves. Ruminating leads us to thoughts like "What do you think you were doing?"

By ruminating on our behavior, we become more likely to blame ourselves, leading to feelings of depression.

The other way to re-examine our behavior is reflection. This consists of looking back at our problematic behavior as if it were a naturally occurring phenomenon beyond our control.

The rain isn't anyone's fault. In that same vein, problems that occur in human society can be thought of as natural phenomena occurring as a result of exceedingly complex interactions.

So if we go back to the criminal, we may ask ourselves: Why was the crime committed? What kind of issues was the criminal facing? Let's objectively analyze the criminal's emotions and the surrounding circumstances.

This idea of treating problematic behavior as a natural phenomenon that cannot be attributed to just one individual is referred to as "externalizing" the problem.

In doing so, the way in which we interpret problematic behavior changes. Problematic behavior and its symptoms are not some meaningless hindrance to be discarded. They constitute a meaningful signal, a person telling you that somewhere in their life, they are experiencing distress.

Focus on the problem, not the person

In the business world, we're often told to blame ourselves before blaming others. However, I prefer the idea of blamelessness.

Blamelessness seems very similar to what you were saying about externalizing problems.

For example, when a client comes to us with a complaint, it doesn't make sense to go straight to "It's the developer's fault" or "It's sales' fault." In reality, the origin of the problem is complex, a combination of issues, so searching for a culprit would prove pointless.

However, if you accept that what's done is done and don't assign blame, you can come to a solution without everyone at each other's throats.

I agree. Rather than track down the culprit and make them pay for their crime, it's more effective to think blamelessly and analyze the problem objectively.

By adopting blamelessness, approaching our problems as a complex combination of factors and sharing them with others, you'll finally see people engaging in deep heartfelt reflection. Ultimately, blamelessness is a prerequisite for achieving this level of reflection.

Anyone can use tojisha-kenkyu

Indeed, and that's the reason we have recently launched a tojisha-kenkyu program for people without disabilities.

Until now, the main targets of tojisha-kenkyu were people with unclear disabilities. However, society is changing rapidly and persons without disabilities are finding themselves dealing with an increasing array of issues they cannot express.

It's distressing to feel a pain that you don't have the words to communicate and the origins of which are unknown to you.

The Japanese version is available at the link below.

Writer

Alex Steullet

Alex is the editor in chief of Kintopia and part of the corporate branding department at Cybozu. He holds an LLM in Human Rights Law from the University of Nottingham and previously worked for the Swiss government.