For the Sake of Culture, Get Rid of the Zombies, Monsters and Robots of Corporate Communication

In the early 70s, psychologist and researcher Albert Mehrabian famously stated that roughly 55% of all communication is nonverbal, 38% is tone, and only a measly 7% is what we actually say. Yet, because we humans are deeply interconnected social creatures with phenomenally powerful brains, that 7% can do tremendous things. Beautiful language can move hearts and minds, start revolutions, build and destroy relationships, and so much more.

I would like to take a moment to focus on that 7%, dig deep into the vocal minority, specifically in the context of professional interactions. How much are our workplace relationships and company culture defined by the language we use?

What we say is who we are

For most people who are active in the workforce, we spend at least as much—if not more—time communicating with colleagues and clients as we do with family and friends. Yet, despite such close proximity, almost every work culture around the world has erected a robust linguistic barrier to prevent even a sliver of intimacy from infiltrating the professional environment.

I've had the chance to work with individuals from around the world, in three different languages and across three continents. Each of these languages—English, French and Japanese—has a designated set of words, expressions and idioms that are only employed in a professional context.

Compared to French and Japanese, English is fairly light on formalities. There is no separate formal word for "you" equivalent to the French "vous," nor is there extreme overuse of the conditional verb tense—albeit English-speaking office workers sure love using "would," "should" and "could." English also doesn't have simple nouns and verbs that change entirely depending on if I am socially positioned above or below my interlocutor, like in Japanese "sonkeigo" (尊敬語) and "kenjougo" (謙譲語).

That being said, even in English, you can immediately tell based on word choice whether or not you're in an office environment. Not only that, you can actually learn a lot about a company's values and organizational structure just by paying attention to how employees talk to each other.

I've come to believe that while office environments need not emulate the intimacy of a group of close friends, we can do a lot to improve company culture by being mindful of language. A few minor tweaks in the way we communicate can go a long way in creating a workspace that promotes open communication, honesty, candid debate and harmony.

Let's take a look at three particularly nasty linguistic culprits of cold, unsympathetic and rigid workplaces: the headless zombie, the bureaucratic monster and the jargon robot.

Give your sentences a human brain

When I started writing columns and blog posts, I wanted to hone my writing skills, so I decided to read through a series of style manuals. The first thing I got from my readings was crippling anxiety, as I realized I'm still eons away from becoming a great writer. The second—and much more productive—realization was that overuse or mistaken use of the passive form sucks all life out of writing. I've found this to be true not just of flowery prose, but also of conversations between co-workers.

The passive form is like a headless zombie, wandering around the realm of the living devoid of all agency or decision-making ability. The lack of a clear human subject makes the passive form a prime tool for escaping responsibility.

I'm sure you've heard—or perhaps used yourself—phrases like "The deadline couldn't be met" instead of "I couldn't meet the deadline," or "A decision was made to no longer pursue this project" instead of "We gave up."

The trouble with passive framing is that very few things that happen around the office are random acts of nature that befall ill-fated employees. Most of the time, people make things happen.

This surgical removal of the human brain from decision-making processes extends beyond just the use of the passive form. Many offices have rules and procedures made who-knows-when by who-knows-who that tend to linger around like the smell of burritos after a particularly hefty takeout lunch. Rules like "a blog post must accompany each product update" or "users need to highlight the recipient name on all bills with a yellow marker."

Modal verbs like "should" or "must" have the power to turn personal preference into company dogma. Maybe I have a personal issue with authority, but when I hear "All receipts must be glued, not stapled," my first thought will often be "Why? Who decided that glue was the way to go? Is there a practical explanation? Where did this unfair treatment of staples come from?"

I'm not saying that all rules and procedures are bad; quite the contrary. I'm saying we should avoid letting practices turn into rules just because one person did it that one way, that one time.

Many companies say they want a culture of responsibility and initiative, but when you listen closely to how people talk to each other, it's all passive forms and modal verbs. If you really want to promote personal responsibility in your company, purging these headless zombies is a great place to start. How can you expect your employees to be proactive and own up to their decisions when they're fighting for survival against a headless horde?

The project deadline didn't mysteriously fail to be met because of the rare alignment of Jupiter and Mars. Bob failed to meet the deadline, and that's OK. Bob's busy, I get it, I understand what truly happened and we can move on.

Don't say: All drafts must be submitted a week in advance for review.

Say: I'd like you to submit your draft a week in advance, because that's how much time I need to review it.

Be weary of the lumbering monsters of bureaucracy

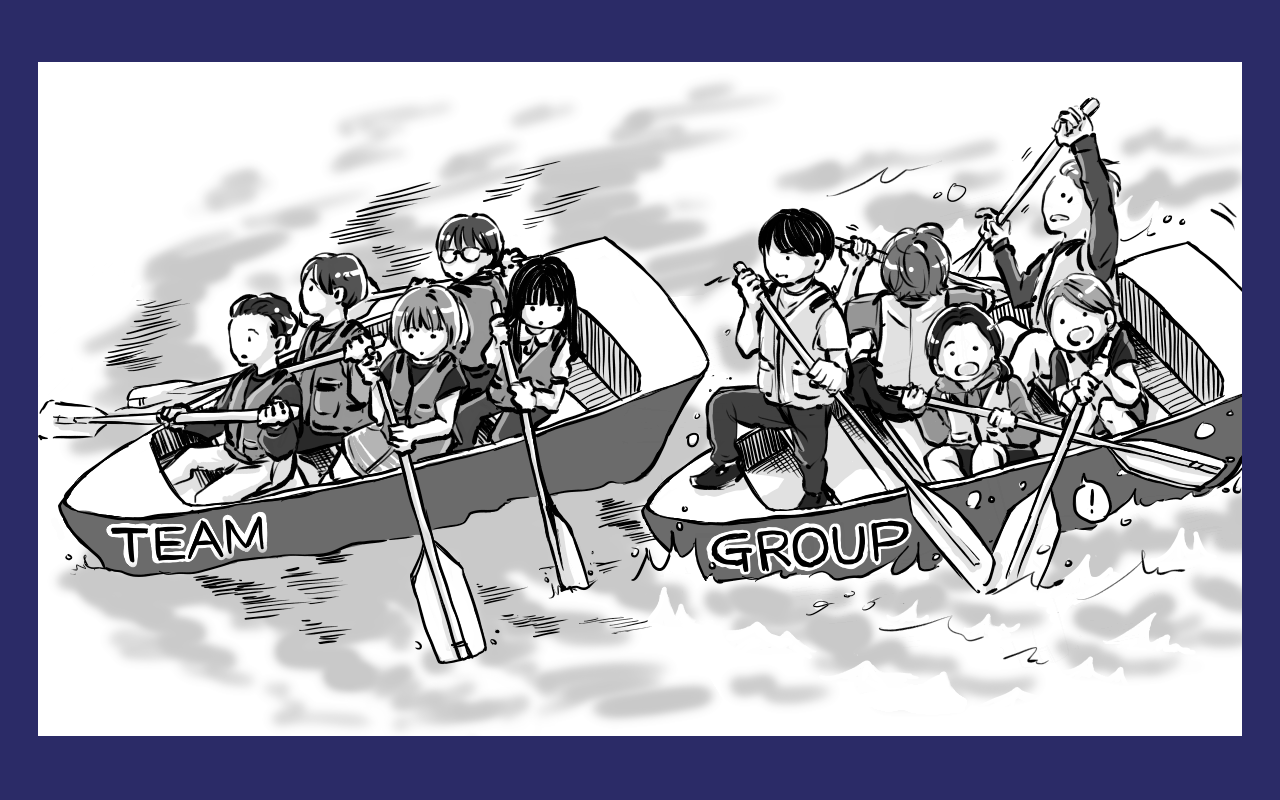

For better or for worse, the human mind is great at dividing the real world into imagined categories. Modern companies have departments, sections, divisions, units, teams—much like the military, but without the brass. These categories are often seen as helpful in order to distribute tasks, determine responsibility and manage processes and workflows.

However, we must never forget that categories are not physical beings; they do not exist in the real world. The HR department is not some overgrown mutant creature that I talk to when I think we could use a better coffee machine (seriously though, we could use a better coffee machine).

I will readily admit that saying "the HR department" is much more convenient and usable than having to say, "a group of people collectively referred to as the single fictitious creation of our collective imagination that we have agreed to call 'HR department.'" When dealing with a large team, designating it as an entire category can be practical, efficient, and even helpful in developing a sense of unity and purpose. However, too many people label their own decisions as those of a category, as a way to give their actions more weight while dodging personal responsibility.

The difference between saying, "The Social Media Promotion Team decided" and "Bob decided" is the weight and authority carried by the label. Humans are invisible as long as they hide behind the bureaucratic monster—I don't know if this "team" is a full regiment of Twitter experts or just Bob all by himself.

Choosing to set the subject of my sentences as the monster rather than the human says something about my company's culture. Where colleagues are systematically referring to themselves as a collective, we tend to see an "us versus them" mentality. The delay is not Bob's fault, it's the team's fault, therefore that entire team gets perceived as lazy and underperforming.

In addition, bureaucratic monsters tend to be large and slow-moving; hampering progress and agility. Because monsters are fictitious, much like zombies, they can't make decisions and aren't open to discussion or debate. Worst of all, we tend to stack these monsters on top of each other to form a hierarchy: the double illusion that is the corporate pyramid of monsters.

In contrast, if I say that I decided something—me, the human—I open myself to debate and discussion. I become vulnerable, accept responsibility for my own decisions, and create an opportunity to talk openly with you, responsible for your own decisions. The slow accumulation of these individual acts of agency is what leads companies to collective improvement and progress.

To sum up, if you want your company to embrace the values of honest information sharing and debate, you may want to pull the curtain next time you recognize Bob's voice resonating from behind a bureaucratic monster.

Don't say: The HR Department requires that you submit your annual performance reviews by the end of the week.

Say: I'd really appreciate if you could send me your annual performance reviews by the end of the week, so that I can get to work on next year's salaries.

Unplug the heartless jargon machine

The words we use can say a lot about our education, competence, and perhaps even intelligence. However, complicated language is not evidence of a sophisticated mind. Just because I'm in a corporate setting doesn't mean that every word I use needs to contain more than four syllables, nor does it mean that acronyms are always more convenient than the words they replace. Corporate jargon is like a powerful robot; it's very tempting to use and we think it can make our work more efficient, but in reality nobody fully understands its functionalities and everything it produces seems cold and heartless.

The point of complex language is to add precision, not create ambiguity. In everyday business, speed and clarity are the drivers of efficiency. Therefore, while it may sound cool to ask if "execution of the social media strategy for Q1 generated increased user traffic to the landing page," we'd probably get the same answer by asking if "the social media plan brought more people to the website." That extra time spent coming up with a perfectly-worded sentence is time not spent moving a project forward.

The pitfalls of overly complicated language become salient in a multicultural, multilingual work environment. Time and time again, I've seen non-native English speakers go blank in the face when more proficient colleagues pepper their speech with idioms, metaphors and hyperbole. Communication is about getting your meaning across to the other person, and therefore requires empathy and understanding of the linguistic and technical capabilities of your interlocutor. In fact, I genuinely believe that spending time communicating with non-native speakers can actually enhance communication ability, allowing us to more skillfully alternate between concise and poetic language without losing accuracy or creating vagueness.

As with every point I mentioned here, there are exceptions. For highly complex technical work, you need highly precise technical language. Sometimes a more elegant turn of phrase can be a display of competence, which in turn increases the chance your audience will pay attention. But in most cases, keeping your message direct, simple and concise will reduce misunderstanding, improve efficiency and foster inclusivity.

Information sharing is essential for companies to thrive in the knowledge economy, but information only has value if it can be understood. We can't have an honest exchange of ideas if I encrypt all of my ideas in jargon. For a culture of openness, diversity and transparency to take hold within a company, we should set aside our natural desire to show competence through language and focus on making sure as many people as possible can easily understand what we have to say.

Don't say: Your quixotic belief that we could eke out a tour de force by shifting theoretical paradigms from stratified intersectionality to holism is a non sequitur.

Say: I don't think that idea will work.

Put people back in charge

Given the tremendous power of language, it's only natural for us to want to use it to our advantage. We all sometimes turn to the passive form to avoid confessing we did something wrong, or hide behind a department name to give weight to our position, or use complex technical jargon to prove that we're an up-and-coming savvy wheeler-dealer.

What these habits have in common is that they serve the interests of the speaker, but not necessarily of the listener or the team as a whole. Communication is an essential component of teamwork, which means the way teams communicate defines how they work together. When language is wielded in a way that benefits the speaker over the team, or the team over the whole company, unity and efficiency suffer. Before long, the entire office space gets invaded by zombies, monsters and robots. The humans in the room are left feeling oppressed, and that oppression can develop into a victim mentality.

I've read enough management books and listened to enough leadership gurus to know that in our knowledge economy, the highest performing culture is one of honest debate and transparent information sharing. However, that culture doesn't appear from the will of a single individual, nor from a well-crafted company slogan. Everyone, from top to bottom, needs to embody those values in their behavior. And what better way to start than by being mindful of how we talk to one another.

Written by Alex Steullet. Illustration by Eiko Matsunaga. Edited by Mina Samejima.

Writer

Alex Steullet

Alex is the editor in chief of Kintopia and part of the corporate branding department at Cybozu. He holds an LLM in Human Rights Law from the University of Nottingham and previously worked for the Swiss government.

Photographer

Eiko Matsunaga

Eiko is an illustrator and designer who works mainly with Kintopia’s twin website, CybozuShiki. She is passionate about making easily understandable and interesting illustrations that match the tone and content of their respective articles.