How Understanding Culture Can Unlock the Business Potential of Global Diversity

Interview with culture expert, author and INSEAD researcher Erin Meyer

We've come to accept as a truism that we're all individuals, with our own strengths and differences. The desire to understand what makes us unique is core to the appeal of things like astrology, personality tests, and online quizzes that tell us our spirit animal in 36 questions.

Yet not nearly as many people are keen on stepping further back to look at what makes their culture unique and different. This lack of perspective can be dangerous in the workplace, when what are simply different patterns of thinking get labelled as weird, wacky or wrong.

Understanding what makes people different is a nuanced and layered issue, requiring a large amount of data and research to distinguish the individual from the cultural. Fortunately, we managed to get in touch with an acclaimed author, researcher and culture expert who specializes in explaining and overcoming difference. Erin Meyer is a Senior Affiliate Professor in the Organisational Behaviour Department at INSEAD, and author of the seminal The Culture Map: Decoding how people think, lead and get things done across cultures. She was kind enough to introduce us to the beautifully complex topic of navigating multiculturalism in the workplace.

When diversity is good, it's great

Alex: Before we get into the nitty-gritty, I'm curious to hear your general thoughts on diversity. Some experts believe organizations should seek out diversity of thought, whereas others believe more in demographic diversity, based on categories like gender and ethnicity. On top of that, we have your field of expertise, which is cultural diversity.

Is cultural diversity always a net positive for businesses, more so than other forms of diversity?

Erin: To start, I don't think that multiculturalism is always a net positive. We tend to have this pollyannaish idea that the more we mix cultures, the better for everyone, without really being thoughtful of the disadvantages that stem from the confusion of multiculturalism.

Cultural homogeneity is great when your objective is operational efficiency, or if you only need to make local decisions about what's happening in your local environment.

This is especially true in high-context cultures like Japan. People from that same culture have the ability to "read the air" as they say: pick up implicit messages and communicate more quickly. What we have seen in these extremely homogeneous cultures is a lot of efficiency, with focus on process and minimizing chaos.

Erin Meyer is an author, speaker, and a Senior Affiliate Professor in the Organisational Behaviour Department at INSEAD. Her work focuses on how the world's most successful managers navigate the complexities of cultural differences in a global environment. She frequently gives keynote speeches to leading organizations and publishes in the Harvard Business Review.

Living and working in Africa, Europe, and the United States prompted Erin's study of the communication patterns and business systems of different parts of the world. Her Culture Map framework allows international executives to pinpoint their leadership preferences, and compare their methods to the management styles of other cultures. More recently, together with Netflix CEO Reed Hastings, Erin published No Rules Rules, investigating the underlying principles necessary for building a corporate culture that is inventive, fast, and flexible.

Erin: The problem is when you're going for innovation; coming up with crazy ideas no one has ever thought before. In that situation, the more diversity the better.

Gender and ethnic diversity will bring some of that. If you're a Japanese company where men are overrepresented, by all means bring in more Japanese women. However, you should also consider bringing in people from other cultural backgrounds.

If you're going for freedom of thought—that clash of ideas that brings in real innovation—I believe multiculturalism is better. There is however a caveat, which is if you don't understand the cultural differences among the people you are bringing in, you risk stamping out the benefits of diversity. Diversity needs space in order to be beneficial.

Contextual awareness

Alex: You mentioned high context cultures like Japan. What is the difference between high context and low context cultures?

Erin: In a low context culture, when we communicate, we value being simple, clear and explicit. When I'm giving a presentation, I will start by telling you what I'm going to tell you, then I'll tell you, then I'll tell you what I told you. The responsibility for communication is on the communicator, and if you don't understand, that's my fault for not communicating well.

In a high-context culture, we believe that good, effective communication is sophisticated and layered. There is not just meaning in my words, but also behind, next to and around what I'm saying. My responsibility as the communicator is to pass along the message, but you the listener also have a responsibility to read the message.

Alex: Given the cultural complexity of high context communication, is low context communication more efficient for business in a multicultural environment?

Erin: It's not more efficient, because efficiency is about speed, and high context communication is faster. If we are all from a high context culture, we don't have to repeat ourselves as much. We don't have to go around making sure that everyone understands. In that sense, high context communication is very efficient.

However, in a multicultural environment, low context communication is more effective. If you work with people from different cultures but don't invest in the bureaucracy of low context communication, then messages become misunderstood, communication breaks down, and we can't be effective.

It's such a funny thing how in low context cultures, the person who looks the smartest is the one who's speaking the clearest, whereas in high context cultures like France and Japan, the smartest person is the one able to communicate on many levels at the same time. It's very hard to explain to someone who grew up in a homogeneous culture that the way they communicate is not going to work in a multicultural environment. But it is possible, and in conducting my research I have seen many people understand and improve.

It also helps if you can kind of laugh at your own culture. Acknowledge that you tend to do things differently because that's just the way your culture is, but that you're making an effort to understand and adapt.

Alex: When reading your book, it struck me that you mention quite often self deprecation as a sort of cultural bridge, but I'm not convinced that all cultures are that good at self deprecation.

Erin: That's true. One of the interesting things about Japan is that although people are very humble—a quality which generally lends itself to self deprecation—it's also an extremely formal culture. Bringing humor into a conversation with people who you don't have a close relationship with could be awkward.

In that situation, it could be good to acknowledge cultural differences more formally. For example, if you know you're going to have a multicultural meeting, write to everyone in advance: "This is a multicultural meeting, so we will focus on being as explicit as possible. Take time to repeat key points, and make sure everybody understood the message as intended."

Alex: That's great advice! I come from a culture where humor is usually very sarcastic, but when I moved to Japan I realized sarcasm just isn't a thing here. There have been times where I tried to be self deprecating through sarcasm and people thought I was just a negative person.

Erin: Yes, you end up having to say "Wait, wait, that was a joke!" which in turn ends up ruining the joke. Where you're from, the French-speaking part of Switzerland, is also a fairly high context culture. That gap in humor is a great example of how, when you try to bring cultural cues from one high context culture to another, it just doesn't work!

Talk about it. Laugh about it.

Alex: Even if you have good intentions and try to be as clear as possible, cultural misunderstandings are still inevitable. From an organizational standpoint, what can be done so that those misunderstandings don't completely derail your business?Erin: I would encourage people to talk more openly about cultural differences. The more we talk, the more we understand what's going on around us, the more we're willing to give people the benefit of the doubt. Once we make an effort to understand that a misunderstanding may have been cultural, we become more flexible, which helps our business.

Let's take an example. You work in Japan, I'm from Minnesota. Even people from Minnesota know that Japanese culture is hierarchical. What they may not know is that Japanese decision-making processes are consensual. So when you bring together people from Japan and people from Minnesota, the Minnesotans may get confused, wondering why the Japanese are taking so long to make decisions despite being a top-down culture.

In that situation, when there's a gap between your expectation from what you know about a culture and what you actually observe, talk about it. Sit down with the people from the other culture and ask them what's going on. Tell them that you were expecting faster decision-making, but there may have been a cultural misunderstanding, so you need to reevaluate how you will make decisions together moving forward. Map your respective cultures, talk about the big gaps and how you can work through them.

Also, laugh as much as you can. One thing I can tell you, that I've witnessed from companies and organizations that have succeeded at becoming multicultural, is that they don't let cultural differences become a big deal. They know how to talk and laugh about them.

Drawing up a culture map

Alex: You mentioned the importance of mapping cultures to understand where there are gaps, but culture is infinite. How do you know where to map?

Erin: The cultural mapping system I use breaks culture down into eight behavioral scales. We look at things like how we build trust, or how we make decisions—the details of each scale are in my book, The Culture Map. Our team conducted 180,000 interviews in 62 countries so that we could position each of those cultures on our scales. Once you know the position of a culture on all eight scales, you have it mapped out.

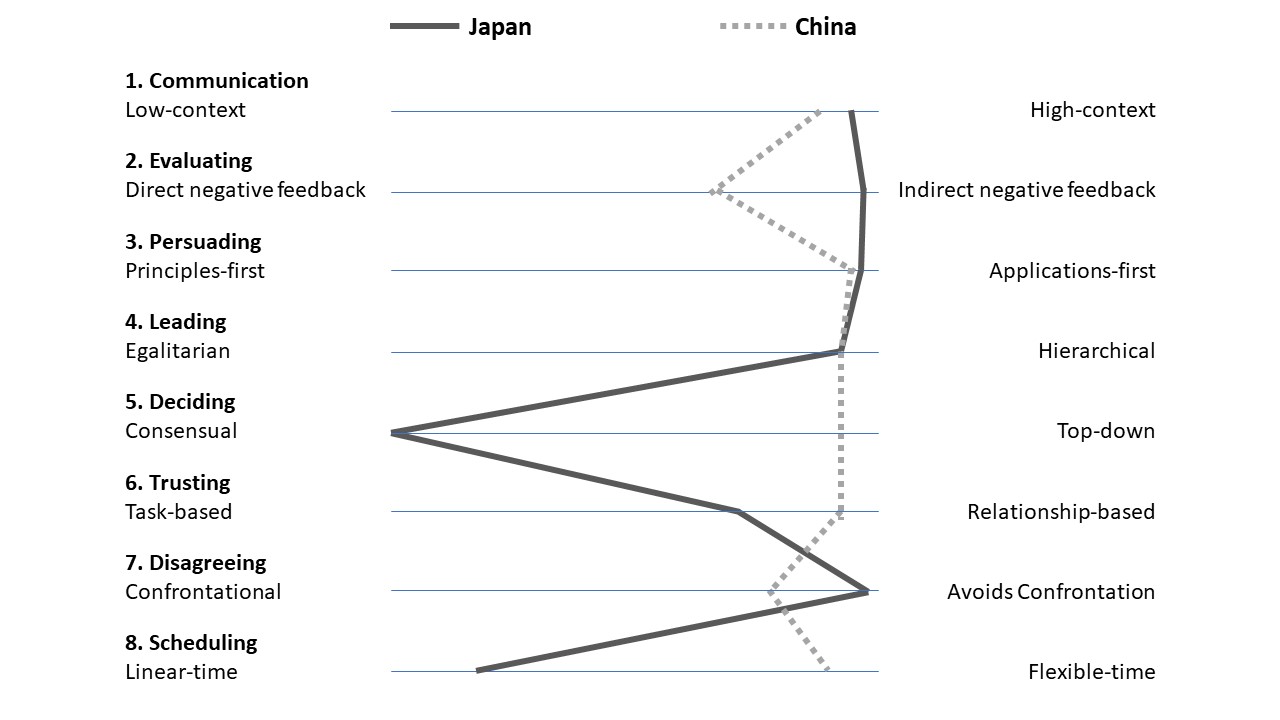

Let's take an example. We mapped out Japan and China, and noticed that on six of the eight scales, they're rather close. For instance, both cultures are hierarchical and value relationships. There are small differences, but relative to other cultures they're pretty close.

An example of a culture map for Japan and China.

Erin: Then, on two of the scales we see massive gaps. The Japanese value punctuality and structure, while the Chinese value flexibility. The Japanese are very consensual, whereas the Chinese make quick top-down decisions.

You can do this kind of mapping with any two cultures. Looking at the similarities and differences will help you start to understand how cultural elements are impacting your team, which in turn can lead to discussions on how to work more effectively.

Alex: Before you map out a culture, how do you know if what you're observing is really a cultural trend, as opposed to an individual trait or demographic tendency?

Erin: This is a very important point. Just because we work across cultures doesn't mean everything is cultural. I'd say there are four different levels that can influence a person's behavior.

The first level is our common humanity. We all have the same psychological drivers, like jealousy or pride, independently of who we are or where we're from.

The second level is where we come from, our culture. How we were raised and how we were taught to see the world. Culture impacts things like the way we communicate and how we build trust.

The third level is organizational. We work for organizations which each have their own cultures, and those cultures also impact us.

The final level is individual. Every individual has their own tendencies. Even twins raised in the same family will have different personalities.

When we are working internationally and find ourselves dealing with something we find awkward or inappropriate, we need to ask ourselves what level that behavior is coming from. Is it cultural, or is it just this individual? But in order to be able to begin to ask that question, we need to understand cultural differences.

Eventually we learn to recognize cultural patterns. When we work with enough people from a certain culture, we begin to notice that everybody or most people have a certain common way of doing things. My work in The Culture Map is to use a large amount of data to identify and classify those patterns. With that baseline, if you notice someone who you think is slow at making decisions, you can look back at the map and determine whether or not it's a common tendency from their culture, of if this person in particular is just slow.

So that's one way you can know: educating yourself on different cultures.

Alex: That's really interesting! What if we still have doubts though, even after educating ourselves?

Erin: That's when you should ask a lot of questions. I would like to emphasize the importance of showing curiosity and humility when working with other cultures. You obviously don't want to go around callously asking questions like, "Yesterday you were really direct, is that a cultural tendency or is that just you?"

Instead you can frame it like, "I was with this Swiss interviewer yesterday asking me kind of aggressive questions. You're from Switzerland, tell me, is that common in your culture?" Or alternatively you can ask for advice on dealing with a difficult cultural situation, like I could ask you about how to give feedback to another Swiss person. Find people from the cultures you work with and with whom you're comfortable talking about these issues.

As a society, I think we don't talk about culture enough. We don't ask enough questions.

Knowing when to adapt

Alex: When you do notice a cultural difference, I can see two different ways of dealing with the situation.

For example, I have American colleagues, and their culture involves always giving very positive feedback. In the French-speaking part of Switzerland, we tend to be much more critical.

When I'm in a situation where I have to give feedback to an American colleague, should I tell them, "You guys probably think I'm a curmudgeon but really it's just my culture," and proceed to give feedback my way? Or should I try my best to adapt to their cultural expectation and be more positive?

Erin: This can get pretty complicated, and it depends on the situation. In the example you gave, you need to do both. Try to be more positive, and if you're not quite getting there, let your counterpart know that your culture tends to be more critical.

The reason it's not enough to just say, "My culture is negative, so I'm going to be negative," is that you obviously know how to have a more effective social interaction, but you're not willing to make the effort. The same way in Japan, where it's not appropriate to give negative feedback in front of other people, you shouldn't ignore that cultural knowledge and tell someone what sucks about their work in front of their whole team.

If you know how to be effective, then it's in your best interest to use that knowledge. If you're not sure you can pull it off, tell them you're trying your best. Use positive words to describe their culture and be humble about your own. In your example, that would be something like, "You guys are so good at recognizing positive things, whereas in my culture, we're just not good at that. I'll do my best." Once you're able to communicate that way, chances are they will welcome your criticism.

The reason I said earlier that things can get complicated is that there are situations where acknowledging and embracing cultural relativity may be the best path to cultural understanding and harmony, but not necessarily to effective management or leadership.

Alex: That leads me to my next question. Are there situations where a certain culture's way of doing things is objectively better for business?

Erin: Those situations do indeed exist. We know for example, based on a lot of research, that in order to have innovation, you need a fertile environment. Two ways to create that environment are multiculturalism and disagreement. They both lead to discomfort and messiness, which is how innovation is born.

I recently wrote a book with Netflix CEO Reed Hastings called No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention. When I started working with Reed, he asked me if Netflix's culture of radical candor could work around the world, including in places with low confrontation, like Japan. I said no. He replied, "Well, I can't give it up, because it's important to the company." So we tried, and I found out that it is actually possible to generate a candid environment, even in places like Japan. The thing is, it can't be ad hoc candor, or ad hoc disagreement. There has to be a time and a place for it.

A concrete example would be we as a team decide that tomorrow at 2 p.m., we're going to have an hour-long debate. At that debate, the leader tells all team members that the more disagreement they express, the more they will be appreciated. Giving very clear instructions is crucial. Tell people that they have to be critical, but also clear and helpful.

Once the interaction is codified in that way, it becomes possible to move organizational culture outside of people's broader cultural pattern. The process is to set a moment, explain what we're doing as clearly as possible, then adapt.

Alex: So in that example, once the meeting is over, people just go back to their comfortable cultural interactions?

Erin: That's right, and they do so without wondering, "Why did that guy attack me? I can't talk to him any more." That messiness goes away because we were clearly told at the outset that unless we participated in disagreeing with one another, we were not contributing to the good of the team.

Multiculturalism has a bright future

Alex: Given that there is more and more research on ways of doing business that are objectively better, are all businesses trending toward the same type of culture? Are we all becoming the same, or is there still room for multiculturalism in the future business world?

Erin: I do not see the world becoming more similar. We can actually track those trends with research.

What we do see is shifts in several areas. For example, the world is becoming increasingly low context. That's a by-product of globalization: Cultures that hang onto high context communication struggle with global teamwork. However, that doesn't mean the entire world is coming together in a single low context point. Rather, the world is shifting.

We also see shifts in what we academics call power distance, which measures the degree to which a culture accepts and expects the unequal distribution of power.

Power distance in cultures around the world is lowering, which means societies are becoming more egalitarian. That's a natural consequence of having the internet, since it's no longer necessarily true that older, more experienced people have more information. As information is democratized, the necessity to defer to authority gets eroded. That doesn't mean every country is the same level of egalitarian, just that younger generations tend to be more egalitarian than older generations, relative to their cultural standards.

Another interesting trend is that until about 15 years ago, when you looked at how people built trust, the world was becoming more task oriented and less relationship oriented. That happened because the U.S. was the global center of gravity and it was pulling everybody else. Now, about 60% of countries are moving toward becoming more relationship oriented, as that is the cultural norm in emerging market countries, whose economic power has been growing.

Those are just a few of the trends we are seeing that show the world is moving, shifting, but not actually coming together and becoming the same. I don't see homogeneity in our future. And honestly, I'm glad.

Written by Alex Steullet. Edited by Ade Lee and Mina Samejima. Photographs courtesy of Erin Meyer. Top visual by Kaori Morishita.

Writer

Alex Steullet

Alex is the editor in chief of Kintopia and part of the corporate branding department at Cybozu. He holds an LLM in Human Rights Law from the University of Nottingham and previously worked for the Swiss government.