Could Japanese Companies Do More To Motivate and Retain Foreign Workers?

As we begin a new year, I find myself once more wondering about my career choices. Just like every year, I went through my year-end evaluation, salary negotiation, and strategic preparations for 2022. I've sat in lots of meetings listening to all the amazing and innovative tasks my colleagues are planning to undertake. And just like every other year, this whole process has got me thinking: Am I doing enough? Am I helping in our team effort?

Do my colleagues really need me?

I don't recall being this conflicted when I started my career as a fresh graduate. The doubts started recently, when I left the job I had in my home country of Switzerland and decided to take up a new challenge by working in Japan.

The company I work for prides itself on having an open environment. I can talk about these doubts to my bosses and colleagues, and I do. Most of them being kind and caring Japanese people, they usually respond with a friendly, "I think you're doing great, you're really helping us out!"

Yet despite their support and positivity, I can't seem to shake my doubts.

I asked around, to my foreign friends and colleagues who were in a similar situation. Turns out, this phenomenon seems pretty common. For some it's even more intense, as I've heard friends recount their frustration, loss of motivation, and even plans for sweeping career changes.

While I can't pretend to fully understand where our unease stems from, I have a theory. It starts with how we're meant to find motivation at work.

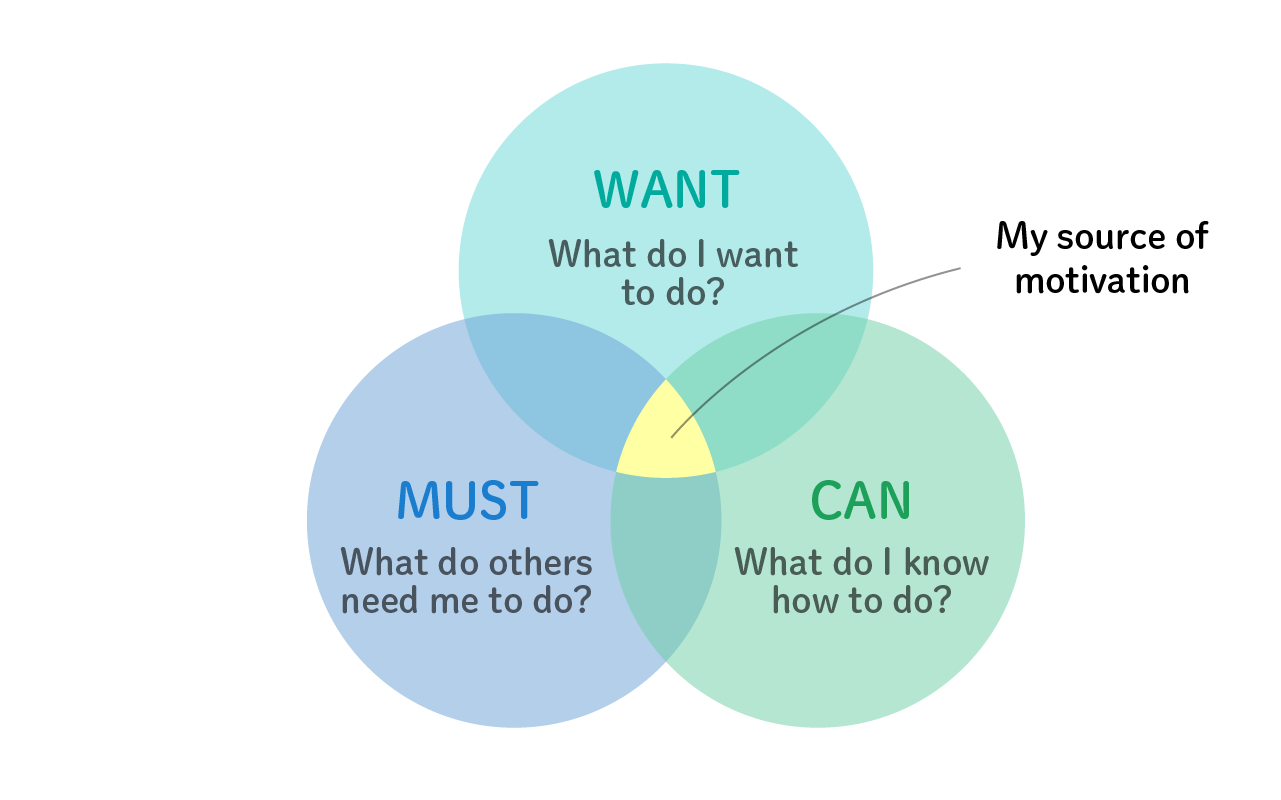

A four-circle Venn diagram

Ever since I joined the private sector, I've been repeatedly amused at how presenters and thought leaders love using Venn diagrams to explain complex interactions. One that I've seen pretty often is this:

As Venn diagrams go, this one's an absolute beauty. The terms are simple, the interactions are clear, and the message is highly memorable. It's a thought leader's dream.

When I applied this to my own work however, I found that something was missing. I love writing, editing and content production, so I've got the "want" covered. My company's been satisfied with my results and want me to keep going, so I've got the "must." As for the "can," I'll leave the ultimate decision up to you, my readers, but I'd like to believe I'm fairly good at what I do.

Where this representation falls short is that it's static, grounded in the present. But life is more than a succession of "now"s. My unease is rooted in a fourth question, a fourth circle to the Venn diagram—one I'd like to call "will."

I haven't been able to find a good answer to, "What will I be doing?"

I thought about lumping "will" into the "want" category, but they're two very different ideas. What I want to do now isn't necessarily what I feel will help me advance my career or develop my craft. Also growth is not purely intrinsic—what I want depends on me, whereas how I grow my career depends heavily on my team, supervisors, and overall work environment.

It's in that fourth circle of the Venn diagram where I noticed the biggest chasm in motivation between foreign and domestic high-skilled workers.

A systemic difference

To find motivation in what you will be doing, you need to know that there's room for growth within your company, which calls for a couple of career fertilizers. The first is difficulty; the best way to learn new skills is to face new challenges. The second is a growth-oriented structure, with managers and team members willing to take risks by giving you room to try, fail, and get better over time.

Back in Switzerland, managers would give their subordinates progressively more important assignments, as well as gradually more independence to carry them out. I started in the public sector by taking detailed minutes at meetings with non-governmental partners. A few years in, I had more opportunities to facilitate those meetings, attend them by myself, and make low-impact decisions. Had I stayed, I would have had more and more say over strategic and budgetary issues, as well as managerial responsibilities.

Thinking back, I always had a straightforward answer to the question, "What will I be doing?"

In Japan, things feel different. I came in as an experienced career hire with skills in multicultural communication. In my company, from the start I was already the best at what I was asked to do. They didn't need me for anything else, so it's been hard to figure out where my job is going. There's always a lingering fear that it may not be going anywhere, which isn't exactly motivating.

The difficulty with difficulty

When I say difficulty is a necessary part of growth, it's important to acknowledge that there are two distinct types of difficulty you encounter at work. Good difficulty provides you with challenges from which you can learn. Bad difficulty wastes time and creates frustration.

An example of good difficulty I experience while working in Japan is the autonomy that comes with competence. In my job creating content in English, I'm the final arbiter for my output, which comes with a refreshing degree of responsibility, alongside opportunities for direct feedback from audiences outside the company. Feedback helps me improve, which in turn allows me to foresee a future with more challenging and rewarding work, answering the "will" question.

A prime example of bad difficulty is daily communication in a foreign language. While my Japanese is slowly getting better, I'll never be as fluent as native speakers. Beyond a certain level, my improvement won't add substantially to what I'm able to do within my company. I was hired to produce work in English, so while better Japanese communication helps my relationships with my colleagues, it doesn't meaningfully increase my output, nor does it produce any answers to the "will" question.

Over time the amount of bad difficulty I experience in my day-to-day life has decreased, but that progress hasn't automatically translated to career advancement. Quite the contrary, since the time I spend trying to understand and respond to my colleagues is time I'm not spending on creating output. This leads to a vicious cycle, as year-end evaluations don't take into account bad difficulty. My boss wants to know what new value I was able to add to the company, not the tasks I'm now able to perform almost as well as my Japanese counterparts.

As a result, I can't give a holistic view of my performance, lowering my chances of getting considered for promotions.

Over the long term, what happens to many foreign high-skilled workers is that they get pigeonholed. They have limited structural support for career advancement beyond the narrow set of tasks for which they were hired. This may be fine for career specialists who only want to grow within their field of expertise, but is a heavy disadvantage for those of us who would like to branch out and develop new skills.

So what can be done?

We can't simply blame management, since it takes a lot more effort and imagination to build a growth support structure for foreign workers. In my company, Japanese managers can more easily envision how a new Japanese hire will progress within the company because the new hire's path will more closely mirror their own. Foreign workers on the other hand are typically doing tasks Japanese managers can't.

The whole reason many Japanese companies hire foreign workers in the first place is to grow the business globally, which inevitably leads to a need for more complex operations. The only way to help a native English-speaking employee answer their "will" question is to provide them support in taking on that complexity.

Unfortunately, doing so comes with inherent risk and discomfort, especially if the manager doesn't have the English-language ability to adequately supervise or evaluate output.

Two common ways I've seen Japanese companies deal with this conundrum is either to hire or promote Japanese supervisors who are proficient in English, or to externally hire more senior English natives to manage complex projects. Both of these solutions effectively block—or substantially delay—career development prospects for international hires already in the company. Also, the level of English considered as "proficient" by Japanese managers can sometimes fail to meet the standard that partners and customers expect for global business communication.

It's therefore no surprise that a lot of experienced foreign workers don't last more than a few years at Japanese companies. From a career advancement standpoint, it simply makes more sense to join a foreign company, or to use your advanced language and business communication skills to get into the consulting business.

At least that's the current situation. I would like to think we can do better.

Take risks to include

Despite the setbacks, from my perspective there are many undeniable benefits to working abroad in a different language and a different culture. The amount of creative thinking and the excitement you get from operating in a diverse, balanced, multi-cultural environment can't be replicated in more homogenous teams. You could even make the argument that what you lose in career advancement, you make up for in personal growth and maturity.

Since working in Japan, I've learned a lot about my strengths and weaknesses, my personal biases, and the limits of my mental fortitude. I'd also like to think I'm more patient and empathetic, as well as quicker at identifying potential sources of tension and conflict between cultures. Not to mention that my broader perspective has made me a more inventive and well-rounded writer.

Yet there comes a time in every career where you have to worry about next steps. If Japanese companies are serious about retaining high-skilled foreign workers and growing their international footprint, I have two suggestions.

The first is to think of foreign staff not as an easy fix to a singular problem in the present, but as a dynamic force for business development that grows stronger over time. Start thinking about career progression from the moment you hire someone. It's tempting to say, "We need to start selling internationally, so let's hire an English-speaking sales rep," but that's not enough. What's your plan for that sales rep after three to five years? Is there room for them to grow? Are you truly open to considering having foreign staff in managerial positions within your company?

Once you have answers to these questions, make sure you communicate them appropriately, and create equitable and transparent evaluation and promotion criteria. If a manager can't reasonably evaluate the quality of their subordinate's work, trust me, the subordinate will experience the unfairness viscerally. There is no easy solution, only the willingness to communicate—get to know your team on a personal level, and make sure everyone understands how their tasks fit into the organization's broader mission.

My other suggestion is to embrace the risk inherent to hiring diverse staff. Miscommunication and misunderstanding is, to an extent, inevitable. It's the price you pay for a boost in creativity and the opportunity to expand globally. Just because a manager doesn't feel like they can have the same degree of control over an employee doesn't necessarily mean that employee should be given less freedom, or fewer challenges.

There's no such thing as "playing it safe" with your international hires. I've witnessed so many foreign workers get frustrated and leave because someone more manageable was promoted in their stead, or because a new hire closed the door to their career progression.

In Japan especially, we're not that big of a talent pool. Every time one of us leaves, taking our institutional knowledge and operational experience with us, our company takes a long-term loss.

A novel experiment

In talking to my colleagues, I realized this phenomenon extends beyond foreign workers. A willingness to communicate around expectations and taking risks for the sake of employee growth will favor anyone who has a different set of skills or a different background from their managers.

We all reach a point where our growth becomes our own responsibility, beyond what our bosses can plan for us. What matters then is whether we're actively involved in the growth and development of the company as a whole, rather than doing our specialized tasks in isolation. A big part of figuring out the fourth circle of the Venn diagram, "What will I be doing?" is knowing, "Where do I fit into what my team will be doing?" You can hire all the diversity in the world, but it won't translate into business success until you also figure out how to have everyone feel included.

Personally, I feel fortunate to be able to have these conversations with my manager. I know we can speak candidly about my output and evaluation criteria, as well as future opportunities to develop my marketable skills and grow my career.

Which isn't enough to dissipate my doubts. When I see the laudable effort my Japanese colleagues invest into coming up with elaborate and ambitious team development strategies, I can't help but think that our English-language operations are lagging quite a few steps behind.

But I also recognize that uncertainty is something I have to live with—an investment in a different kind of future. Blending cultures is a novel experiment for both sides. As long as management is willing to openly communicate about our challenges, include me in future planning, and take some risks for my benefit, I'm willing to set my doubts aside and give them more of my effort and time.

The long-term goal of building a more connected, more cooperative society, is worth it.

Written by Alex Steullet. Edited by Mina Samejima, Yoshiharu Takeuchi and Maui Fukami. The Japanese version of this piece is available here:

For more information on my experience working in Japan:

Writer

Alex Steullet

Alex is the editor in chief of Kintopia and part of the corporate branding department at Cybozu. He holds an LLM in Human Rights Law from the University of Nottingham and previously worked for the Swiss government.

Photographer

Eiko Matsunaga

Eiko is an illustrator and designer who works mainly with Kintopia’s twin website, CybozuShiki. She is passionate about making easily understandable and interesting illustrations that match the tone and content of their respective articles.