Time Well Spent—Moving to a Four-Day Workweek

Interview with Dr. Alex Soojung-Kim Pang

While it's difficult to imagine what the future of work will be like, one thing we can do is go back into the past and look at how people imagined us working today. Our ancestors seemed unanimous in one prediction: The wonders of technology would allow us to work less and enjoy life more.

Yet somehow that hasn't quite come true. Modern workplace culture rewards working unsustainable hours while being constantly available and always giving it your all.

I sat down with Alex Pang, founder of the Restful Company and visiting scholar at Stanford University, to talk about how we got to where we are and put forward what many may see as a radical proposal: moving to a four-day workweek.

Alex: Thank you for taking the time to speak with us. Could you start by telling me about how you became interested in the four-day workweek?

Dr. Pang: Sure! My background is in the history of science and technology, and I'm part of a school of research that looks at scientific practice and the way scientists actually get work done.

I got interested in this particular topic when I was promoting my last book about rest and its role in the lives of creative individuals. I began to realize the extent to which we think of challenges in the workplace, at least in America, as things that are of the responsibility of the individual to solve. For instance, Cheryl Sandberg's book Lean In essentially argues that women should solve problems of workplace sexism by working harder, by leaning in.

I think this ignores the fact that there are deep structural and cultural factors that put hard limits on how much individuals are capable of rethinking work or changing the way that we work.

I started looking into companies that have introduced flexible work policies. I zeroed in on the companies doing the four-day week that aren't reducing pay, productivity or profitability. These companies demonstrate that it's possible to resist the culture of overwork, reorient companies to be more efficient, and offer substantial improvements in employee's working and personal lives.

When I saw these companies popping up all over the world—not just in Nordic countries with long traditions of social welfare or in France where nobody works anyway (according to most Americans), but also in Japan and Korea—I realized there's a book to be written.

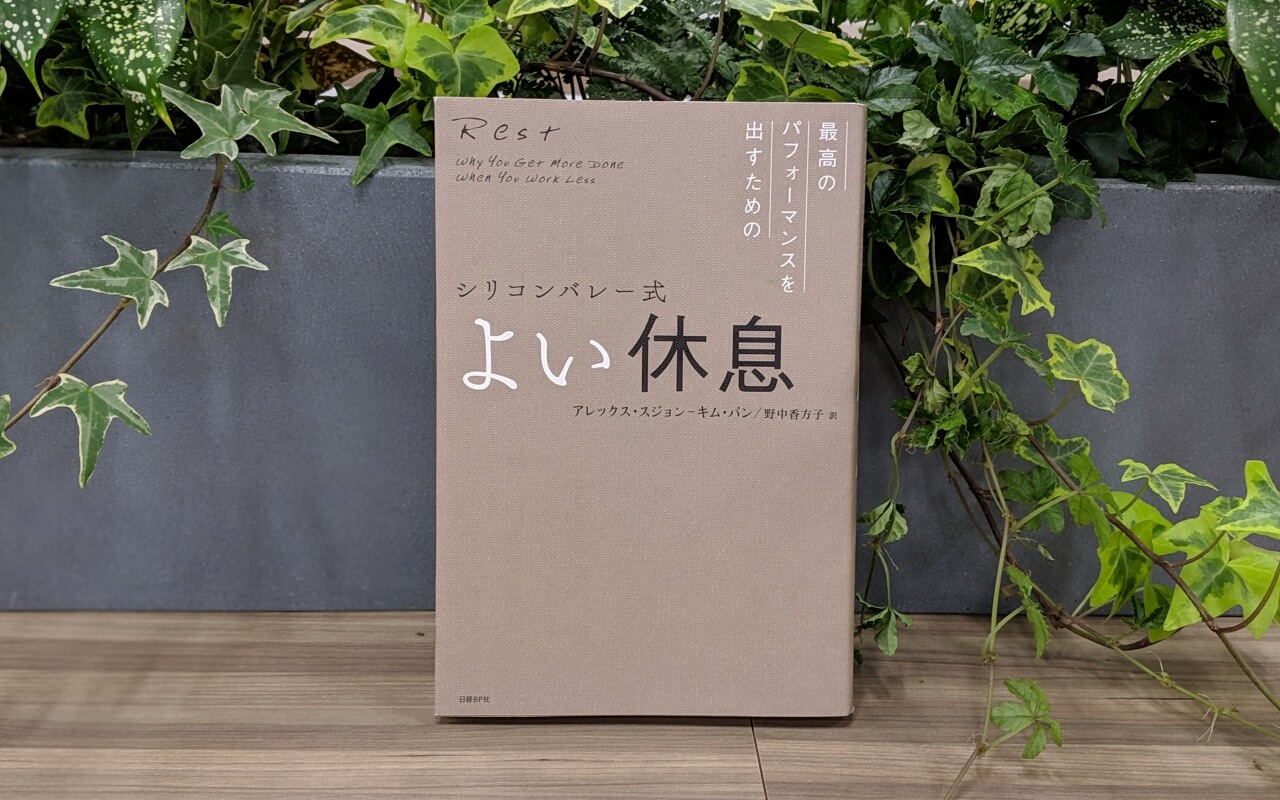

Alex Soojung-Kim Pang is an author and researcher specialized in rest, creativity and productivity. His upcoming book, Shorter: Redesign Your Work and Reclaim Your Time, is scheduled for release in early 2020 and will look into how companies around the world are reducing work hours. His last book, Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less, delves into the importance of rest in the lives of creative individuals. Dr. Pang is a visiting scholar at Stanford University with a Ph.D. in history and sociology of science from the University of Pennsylvania. He is also a consultant and the founder of The Restful Company.

The way we work is broken

Alex: What's wrong with the way we work now?

Dr. Pang: It's a train wreck of misunderstandings about the nature of work that requires people, especially women, to work as if they don't raise children and raise children as if they don't work. It creates conditions that are counterproductive to the aims of companies. But other than that, there's nothing wrong with it! (laugh)

The situation we're in started in the 70s and 80s, when a couple of things happened. It used to be that you joined a company, you paid your dues, you worked your way up, and finally you reached the top. Silicon Valley and Wall Street in the 80s broke that model. You became successful by working herculean hours while you were young, before the market tanked or your skills became obsolete. You had a narrow window where you either failed or became phenomenally successful.

Another thing that happened was that by moving into a knowledge and service economy, work is no longer physically or temporally constrained. We don't come back from the field when the sun goes down. We don't go home when the factory whistle rings.

Furthermore, an awful lot of knowledge work has a highly subjective element to it. You can spend a long time chasing those final pieces of quality. There are hidden economic incentives to overwork, to overdeliver, because you're never sure what constitutes good work, nor how your work is going to be judged. We are encouraged to produce maximal effort all the time.

Technology is another big factor. We can carry our offices around with us all the time. The fact that it is possible to check your email at home becomes the imperative that you must check your email at home.

And then finally there is a cultural element to it. Work has come to play a role in our lives that community, family and religion used to play, as a kind of central organizing force.

Alex: How has the current situation affected the way we feel about work?

Dr. Pang: One of the things we've seen is a reversal of the age-old relationship between success and seniority on the one hand and working hours on the other.

It used to be that the higher up in an organization you were, the less you had to work. This was in a sense a reward for doing well earlier in your career. That's gone. There is a kind of moral imperative now that says overwork is a badge of honor, a hedge against being made redundant. And because it's present at the highest level of organizations, it filters down to everybody else.

Recently, Elon Musk sent an email around 1 a.m. imploring workers at Tesla to remember that they are in an arms race against gigantic, entrenched, horrible fossil-fuel burning companies and that all employees needed to put in extra effort. The email did not mention that Elon Musk himself has a multibillion-dollar payday on the line! I think this illustrates the way in which companies and leaders are willing more than ever to exploit idealism and uncertainty in the service of their corporate goals and personal enrichment.

Another thing that is worth noting is the paradox, pointed out by Dr. William Davies, sociologist at Goldsmiths College in London, when it comes to demands on the part of companies to engage in performative positive psychology. You're supposed to always look as if you love your job, even though that affection is increasingly not reciprocated. They have taken the lesson that happier people do better at their job and have weaponized it. Rather than having deep structural changes to make people happier, they do superficial things, like play music at the beginning of a shift.

This has led to companies adopting the message "The floggings will continue until morale improves," rather than doing things that make people more content with their lives over the long run.

Less time means more focus

Alex: Does reducing total working hours have that long-term effect on happiness? And if so why a four-day workweek? Couldn't we envision having four-hour workdays?

Dr. Pang: One thing at a time. A four-hour workday is a great goal, we may get there eventually. Certainly, economists 100 years ago thought that by now we would all be working 15 or 20 hours a week. The fact that we aren't feels like one of those sci-fi movies where you discover you're stuck in the wrong timeline. The challenge now is to get back on the right timeline.

For many people the four-day week strikes a good balance, offering additional free time while still allowing for good work. This kind of balance is harder to find in flexible work schemes.

Flexible work options are terrific when done in a company that understands how to do them and in which they are widely used. However, there have been several recent studies in the U.S. and the U.K. that have found some disturbing unintended consequences.

One of them is that there is a cultural penalty to using flexible work when just a minority does so. Those who use it are put on fewer interesting projects, or they're not promoted as quickly; there is the sense that they are not as committed as the person staying until 9 p.m.

Another downside is that there are measurable stress impacts, particularly for women with children. There was a study that was published earlier this year measuring a variety of biological markers of stress. It found that overall, women with 2 children who were working in flexible environments showed 40 percent greater levels of stress than men with no children, and 20 percent more stress than women with one child.

Another downside of flexible work is that it requires an enormous amount of coordination. People using it are responsible for informing their colleagues and making sure they are not inconveniencing the system. This is a whole layer of labor that doesn't exist in a four-day workweek, because in most circumstances everyone is in the office Monday through Thursday.

In well-run companies, the four-day workweek creates a set of challenges that have to be met collectively, leading to unintended benefits rather than unintended costs. I worked with about 100 companies of up to 1000 workers and these benefits were present everywhere. However, because it's a decent but not gigantic sample set, I can't say if the effects are bigger in one industry versus another, nor how they change with scale.

Alex: What have the effects of these policies been on companies' bottom line?

Dr. Pang: Of the companies I've worked with, only 3 or 4 moved away from the four-day workweek. Of those, only one did so because it was losing money. The others did so for more cultural reasons: for example, a video production company where the office felt too empty because you had many people out of the office on assignment, leading to a loss of social life at the office.

Most companies are able to maintain profitability. In the case of factories or restaurants, some infrastructural work may need to be done. Restaurants that move to a four-day workweek may need to seat more people to make up their revenues. For creatives companies, the main thing I saw were improved processes, because you need to tighten up the ship in order to do five days' worth of work in four.

You also tend to have improved communication and collaboration between people. With a four-day workweek you have to be more mindful of your time, and work in a more focused manner. In an office, focus is a social resource: my ability to concentrate depends on your willingness to respect my attention. If you want to leave Thursday afternoon, I have to be able to get my work done and vice versa. That translates into much shorter meetings; the hour long all-hands meeting turns into a 10 minute walk-in with just a couple of key people. When it comes to things like email and Slack, people don't get rid of it entirely, but are more thoughtful of how much time is spent on it and who needs to be communicating about what.

The other thing is that people tend to redesign the workday, with most of the important tasks taken care of during the first half of the day. In the morning you only have short coordination meetings, and then you don't have client pitches or other meetings until the afternoon. This allows for three or four solid hours during which everyone can focus.

There are a hundred and one other things that specific companies can do depending on their industry, but just these three things—getting meetings under control, redesigning your workday and getting technology under control—will allow you to take advantage of the improvements in technology that we already have, but the benefits of which have been buried under bad management.

These practices have also led to people reporting higher levels of satisfaction. We've all had that experience of having 5 o'clock come around and wondering, "What did I do today?" Designing the workday for that not to happen will make people happier.

Don't forget the value of time

Alex: Wouldn't it be possible to implement these time-optimizing measures in a five-day workweek?

Dr. Pang: Occasionally I will get people who say, "This sounds awesome. Can I get all this stuff, but in five days?" To which the answer is: That completely misses the point.

The four-day workweek is a social contract between the employer and the employee. In exchange for the employee working in a more focused and productive manner, the employer will think of time not as a commodity to be grabbed in as large a quantity as possible, but rather as something precious to be conserved.

Can you get these same gains by playing Pharrell Williams' "Happy" and giving gift cards? You know your business better than I do, but the odds are, you can't.

Further, asking the question "Why do we work five days a week, can we do this differently?" opens up a space for people to ask, "What else could we do differently? What other things do we take for granted that we could rethink?"If you are in a purely transactional business or you're a commodity producer, you don't have to worry about this kind of thing. If ultimately what you want to do is replace your entire workforce with robots, then this is not going to interest you.

On the other hand, if you're working in a creative industry where there is real value in having people be bold and ask these fundamental questions, and actually come up with strategies and solutions that address them, then moving to the four-day workweek can have a powerful effect.

I've seen plenty of creative agencies keep the clients that they have and attract new ones even while working 20 percent less, in an industry where people have traditionally pulled all-nighters until late in their careers. This is a real testament to the effectiveness of this approach in improving the quality of people's work and the quality of their relationships with their clients.

Alex: So it really is about the mentality of the people who are implementing these policies and their willingness to rethink time as a scarce and valuable resource rather than as an expendable commodity.

Dr. Pang: Yes, absolutely.

Today's experiment, tomorrow's wave

Alex: When it comes to the companies that made the transition successfully, what would you say were the keys to their success?

Dr. Pang: In addition to reorganizing the workday and getting technology under control, one thing that everybody is doing and has been essential for their success is managing expectations of clients. It's always a big worry, but it often turns out to be less of an issue than people expect. As long as you're clear about what clients need and that you make clear that you are putting in place backstops to deal with emergencies, then clients are often very supportive, because it turns out they see you as solving a problem they have themselves.

It's one thing for your clients to read about this going on in Scandinavia. For American companies, reading about something happening in Sweden is like reading about the elves in The Lord of the Rings. Whereas if you're a company they've worked with for years, they know you, they know your culture, so if you can make this work, maybe they can too.

Another thing is that when it comes to creative agencies for example, a four-day workweek can be a very powerful piece of branding. Being able to do in four days what other companies do in five suggests you really know what you're doing. It implies a certain ability to think creatively and out-of-the-box.

Also treating it as an experiment that you're going to do for a while and that could end in success or failure serves to clarify everyone's understanding. It's not simply a perk you're giving people. It should offer mutual benefits to the organization and to the individuals.

Finally, being as clear as you can about your key performance indicators early on is important. These are not arcane measures, but ones you're probably familiar with, ought to measure anyway, and probably are already measuring. How's your cash flow? Is work being delivered on time? If you see those numbers staying stable or going up, that's good. If not, that's when you have to make some hard choices.

Alex: You mentioned that most of these experiments tend to happen in smaller companies, why is that?

Dr. Pang: I don't think there are barriers that make this difficult for big companies. It happens in smaller companies because cultural innovations (and process changes) are easier to try out in smaller companies. From there, those innovations filter into larger ones. When Apple was 30 people, it had an open office with bean bags.

The fact that companies can scale quickly these days means that five years from now, today's quirky experiment by this little company in Palo Alto can be the new wave among Fortune 100 companies. There is nothing that would prevent an Oracle or a Google from going to a four-day week right now. These people are incredibly smart, they can figure out how to do this.

The two biggest companies that I know are doing this are ZOZO Inc. in Japan and Woowa Brothers in Korea, both of which now have about 1000 employees. These companies are continuing to grow and, as far as I know, have no plans to move away from their shorter workweek. In fact, they're doing all kinds of things to make sure that new people learn how to work this way.

Could this work globally?

Alex: For countries with rapidly aging populations, wouldn't reducing the number of working hours slow down their economies?

Dr. Pang: If you set maintaining productivity as a goal, the economy may not slow down. Also, there are two significant long-term impacts.

The first is that careers themselves can get longer. I've had a number of people say, "I'm working four days rather than five because it lowers my stress level; I have more energy, I'm not going to burn out doing this job, I'm not going to need to retire. I'm doing something that I really like and I could imagine doing it 20 years from now, whereas working the way I did before, I couldn't imagine still doing this in five years." At the larger scale, having people stay in the workforce longer could be a significant benefit.

The second is that lowering work hours can prompt us to reimagine the way companies use technology. We would have to stop thinking of how to extract the maximum amount of time from workers and instead think of how technology can increase productivity and how to share those gains with workers. Stop thinking of mobile technologies as a way to email your workers at 10 p.m., but instead as a way to create mobile offices that people can shut down and get away from at the end of the day.

In the current work culture, if you want workers to steadily work longer and longer hours, the benefits of a robot are self-evident. If on the other hand your challenge is to work the fewest possible hours to still delight your clients and maintain a happy workforce, then you implement that same technology very differently. One of the great benefits the four-day workweek gives is that it leads to a way of thinking about labor and technology that could address some of the looming problems that automation will otherwise undoubtedly cause.

Alex: Another problem is that a lot of employees rely on overtime to raise their salaries. For these workers, wouldn't reduced hours mean reduced pay?

Dr. Pang: You've got to get rid of overtime, or rework the rules about when overtime kicks in. For industries where a substantial amount of earnings comes in the form of overtime, or if you charge by the hour, then this is a real problem.

I've had a couple of conversations with law firms, which will traditionally charge by the hour. To go to a four-day workweek is inconceivable for them, because they've had drilled into their heads the idea that you maximize billable hours no matter what. Recently we've seen a slow shift from hourly billing to project billing, which would allow for a four-day workweek, but you absolutely have to think of what percentage of your workforce gets a substantial portion of its salary from hourly pay.

In Korea they recently put in a rule capping weekly working hours at 52. It's been great for salaried workers, because they get to have "life with evenings," as one politician called it. But some hourly workers have seen their wages drop by 25 percent or so, which is a cautionary tale of the problematic implementation of what is in principle a good policy. It's important to keep these issues in mind so as to not accidentally impoverish part of your workforce.

The Japanese version of Alex Pang's Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less.

Everyone has a role to play

Alex: This shift seems like it would necessitate dedication on all levels: workers, employers and governments. If you could give one recommendation to each of these players, what would it be?

Dr. Pang: For employees, it is a tremendous opportunity for people who like their work but seriously worry about work/life balance, or burn out to solve those problems. Also, meeting the challenge of the four-day workweek is great because you have to take the thing that you do pretty well in five days and figure out how to do it in four. You're taking essential skills in self-management, planning and organization, and you're applying them elsewhere in a way that will improve your life.

For leaders, I would say it's a great opportunity to become a more sustainable and better-run company. In the end, 90 percent of the work of figuring out how this is going to get implemented is done by the workers themselves. Let's face it, as an owner and manager, you don't know what your skilled workers really do and how they could do it better. It's up to them to figure it out, and they will. What you're going to end up with is a more motivated, happier and more stable workforce. New hires will generally be more senior than you've had in the past. You'll probably also get a higher proportion of women, particularly working mothers for whom the four-day workweek is life-changing.

For governments, it would be important to craft policies that recognize what companies are doing and minimize the emerging unintended consequences. Rules about overtime and policies that substantially affect salary versus hourly workers are clear examples of things to think about. As we have more of these experiments, we'll see other examples of pitfalls to be addressed.

Alex: One last question, where can our readers find more information about the four-day workweek?

Dr. Pang: In my previous book I talk about the concept of deliberate rest, and on my website, I've been tracking these stories. I've also got a podcast where I've been interviewing heads of these companies, giving them a chance to tell their stories.

If you want particular companies, the most interesting example for me is a company called IIH Nordic. They're an SEO company that has been doing the four-day workweek for a couple of years now, and they're a terrific example of a company that measures everything. They're very clear on what the benefits are.

Alex: Thank you very much for taking the time to speak with us. You've certainly given us a lot of food for thought, including for our own company.

Dr. Pang: Thank you.

Interview by Alex Steullet. Edited by Richard Ho. Photographs courtesy of Alex Pang.

Writer

Alex Steullet

Alex is the editor in chief of Kintopia and part of the corporate branding department at Cybozu. He holds an LLM in Human Rights Law from the University of Nottingham and previously worked for the Swiss government.