The Radical Potential of Civic Mindfulness

Interview with Dr. Ronald Purser, professor of management at San Francisco State University

It's all in my head—or so I've been told.

Like the cliched plot of a horror film, the keys to lowering stress, building resilience, combating depression and finding happiness were inside the house this whole time. Or at least that's what I'm told by the denizens of the modern self-help movement, credited with importing life-changing techniques from around the globe to bring color to the monochromatic lives of average office workers.

The trendy new hue in this rainbow of inner peace is known as mindfulness, and in the past few decades it has taken over the corporate world. Proponents of mindfulness promise a panacea: techniques anyone can use to deal with stress and anxiety by shutting out the world and focusing inward, becoming one with the present moment.

I tend to be skeptical of any method that promises me life-changing results from the comfort of my couch, but mindfulness has something different. Its therapeutic claims are backed by science.

So is that the end of the story? Is mindfulness the one change I need in my life? Before booking a six-week meditative retreat, I decided I had to talk to at least one person who wasn't drinking the mindful Kool-Aid.

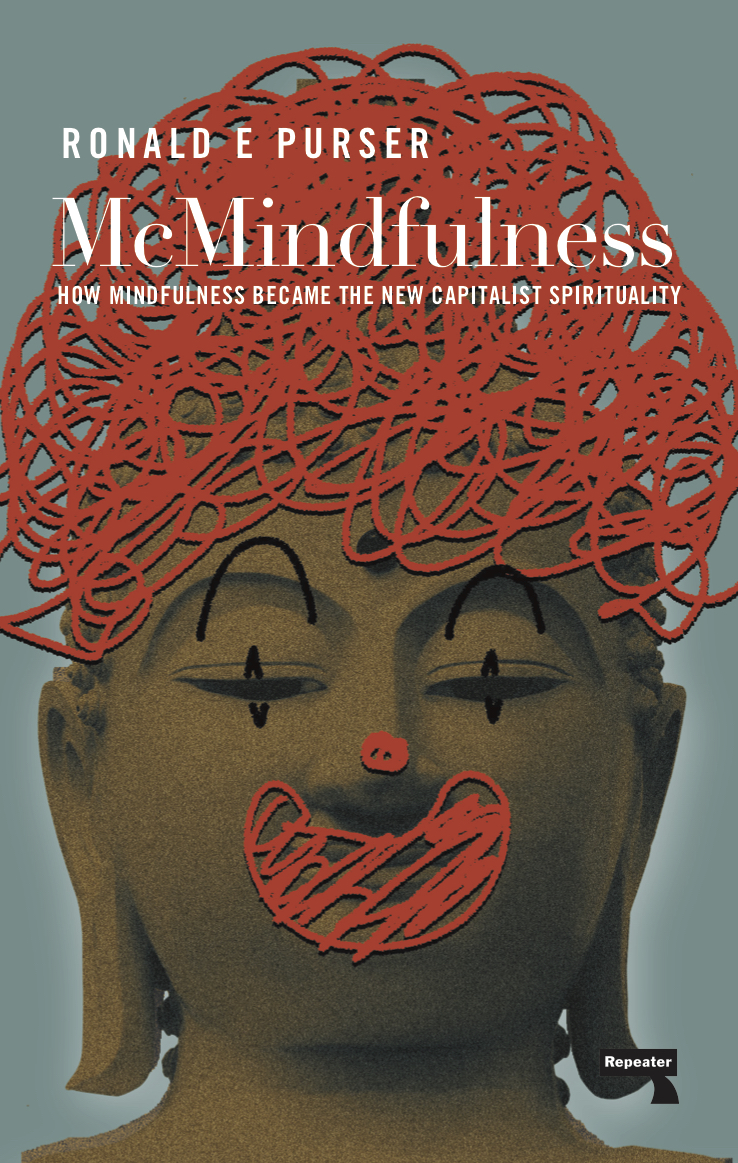

Ronald Purser is a professor of management at San Francisco State University and the author of McMindfulness: How Mindfulness Became the New Capitalist Spirituality. We sat down to discuss what mindfulness is, where it came from, and whether it's truly a one-way track to happiness.

First, focus on your breathing

Alex: Let's imagine a scenario: I'm a new hire at this giant tech company. My work is stressing me out, so my boss recommends a mindfulness program. What can I expect from this program?

Dr. Purser: First, you should know that you're being sold a marketplace commodity.

You would be trained in a few breathing techniques like watching your breath, maybe paying attention to various sensations in your body. These techniques are meant to help you relax, calm down, and notice your thoughts and feelings as they arise without attaching to them, without following the stories that you're telling yourself.

These programs can last anywhere from a few hours to five or six weeks. You would probably be doing it with other people, perhaps in a group.

And you would also be told a certain narrative about stress. You would be told that stress is inside your head, it's because you're overreacting to circumstances, because you don't know how to self-regulate your emotions.

You would be coached into engaging in these practices as a way to help you cope and adapt to the working conditions and the corporate organizational culture in which you find yourself. The implicit message is that you're responsible for managing your own well-being, mental health and stress, and we have a program to help you do that.

Ronald Purser is a professor of management in the College of Business at San Francisco State University. His research explores the challenges of introducing mindfulness into secular contexts, particularly with regard to modernity, Western consumer capitalism and individualism. He received his doctorate in organizational behavior at Case Western Reserve University. Dr. Purser is an ordained Zen Dharma teacher, and the author of McMindfulness: How Mindfulness Became the New Capitalist Spirituality.

From being one with everything to being all about me

Alex: Where does modern mindfulness come from?

Dr. Purser: Mindfulness itself goes back 2600 years to the teachings of the Buddha. It was documented in the Pāli Canon—the earliest recorded teachings of the Buddha—in a particular text called the Satipatthana Sutra, which translates to "core teaching on mindfulness." That text is really the instruction manual for mindfulness meditation in the Buddhist tradition.

It wasn't until the 19th century that a British Oriental scholar by the name of Thomas Rhys Davids, who happened to be in Sri Lanka, translated the sutra. He knew Pali and Sanskrit, and he really struggled to find an English translation for the Pāli word Sati, which we now translate as mindfulness. The original Pāli word has many connotations, mostly to do with recollection, remembrance and calling to mind.

Specifically, this "calling to mind" referred to certain doctrinal instructions and contemplative reflections that were in the Satipatthana Sutra, such as the teachings of the Buddha and the nature of the Four Noble Truths.

In the canonical description of Sati there is a differentiation between right mindfulness, Samma, and wrong mindfulness, Miccha. Right mindfulness will bring to mind skillful mental states that will reduce suffering or not cause suffering, and avoid unskillful mental states—emotions and feelings that would lead to suffering.

A big part of mindfulness is the notion of discernment, sampajaña, which translates to "clear comprehension" and means to clearly comprehend what is going on in the mind. Mindfulness wasn't a passive nonjudgmental attentiveness to the present moment—that's the modern operational definition of mindfulness and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). It was very actively engaged in discerning what was going on, and recollecting words and teachings from the past.

That's very different from what you see in modern therapeutic mindfulness practice. Mindfulness included retrospective memory of the past, but also prospective memory of what the consequences of your thoughts, intentions and behaviors would be in the future. The cognitive dimensions of mindfulness involving judgment and discernment have been downplayed, or even ignored.

We must also remember that there were three trainings in traditional Buddhism: ethics and morality, meditation, and wisdom. Mindfulness has been separated from this integrated, comprehensive approach to spiritual development.

Alex: How did modern mindfulness become separated from its spiritual roots?

Dr. Purser: It's a long history of decontextualization.

The modernization of mindfulness goes all the way back to the Theravada meditation lay revival movement, particularly in Burma when it was under British occupation.

At the time, meditation was reserved for elite monks. It wasn't until Buddhism came under threat in countries like Burma, Thailand and Sri Lanka that meditation was intentionally opened up to lay audiences. It was a form of political nationalistic resistance against colonialism and Christian missionaries.

The elder monks leading this reform wanted to appeal to Western sensibilities by saying Buddhism isn't a religion, it's actually a science of the mind. Mindfulness was intentionally reframed as something nonsectarian, universal, and compatible with Western rationalism and science.

Fast forward to the early 60s, when you had Westerners in Burma and Thailand in the Peace Corps who were starting to learn these methods—people like Jack Kornfield, one of the co-founders of the Insight Meditation Society who also has a Ph.D. in clinical psychology. They learned these methods, brought them to the U.S. and psychologized them, effectively stripping them of their Asian cultural baggage.

Upon reaching the U.S., modern mindfulness became heavily influenced by American transcendentalism, which was built around this idea of disenchantment with industrial society—that we've lost touch with nature.

What we're left with today is a small sliver of the original techniques, which has led to the modern understanding of mindfulness as a therapeutic practice that offers a helpful sense of calm and quietness. Through this process of cultural translation, the individual's personal experience became valorized. If you practice mindfulness you are told to be the judge of your own personal individualistic experience.

Alex: Was mindfulness not meant as an individualistic practice?

Dr. Purser: The whole purpose of mindfulness was to uproot the attachment to the self. It was meant to unveil our primordial delusion: that we feel we are separate, independent and eternally existing individuals. This ties back into the wisdom side of meditative practice. The calming stage was meant to stabilize the mind. Once stable, the mind could observe and ultimately call into question nature of the experiencing self.

In Buddhism, liberation is liberation from the story of being a separate self. We are meant to see that despite appearing separate, all phenomena are, in their true nature, relative and interdependent.

From this realization comes compassion, because if you can see clearly past the delusion of yourself as a separate individual, the sense of boundary between self and other disappears and you naturally become more compassionate.

Modern mindfulness finds itself more in the world of psychology and medicine than in the nature of self and compassion.

The problem with therapeutic mindfulness is that it works

Alex: What are the main therapeutic goals of modern mindfulness, and how did it become a technique in modern medicine?

Dr. Purser: The goals are to reduce stress, calm the nervous system, manage anxiety, and create distance between one's thoughts and one's feelings.

Mindfulness was brought into western medicine in the 60s and 70s by medical experts like Jon Kabat-Zinn and Herbert Benson. They studied mindfulness practices through the lens of biology for Kabat-Zinn and physiology for Benson, disconnected from any kind of religion or spiritual lineage.

Meditation had been part of the western philosophical tradition since ancient Greece, but always embedded in a moral and ethical context. What you see with modern mindfulness is its reduction to an instrumental technique. Without any ethical or moral context, meditative practices lend themselves to any kind of utilitarian pragmatic use. The philosophical notion of equanimity is now seen as just a physiological state which can be measured, studied, and correlated with meditation and mindfulness. It's almost like mindfulness has been put into a Petri dish, disconnected from its contextual ecosystem.

Alex: That seems to be how western medicine operates across the board. It takes a chemical, process or technique from the environment, strips it down to its core elements and applies it therapeutically. Many will then argue that as long as this has a curative effect, what's the problem?

Dr. Purser: That is the most common reaction to my argument. I would respond that there isn't anything inherently wrong with using these techniques to deal with stress.

The problem with mindfulness isn't that it doesn't work. The problem is precisely that it does work. What we should then be asking ourselves is work in the service of whom and whose interests?

To use an analogy from western medicine: there's nothing wrong with treating depression, quite the contrary. The issue arises when you consider depression to be a strictly private disease, stripped of political, social and economic contexts.

This is where corporate and market interests come into play. If you look at the pharmaceutical industry, there is a vested interest in preserving the world view that medicalizes depression to such an extent that you don't question the environment that allowed these diseases of despair to become so prevalent.

The problem is not that people are getting individualistic benefits. It's at the ideological level, maintaining a narrow way of framing human distress. That's why I'm not blaming individuals that are taking up these practices, but am more concerned with the dominant cultural message that happiness is a skill—independent of your social conditions—that you can acquire through self-management and hacking your brain.

There are external factors that could help people become a lot less stressed, such as organizing around collective resources, or changing political and social systems. It also shouldn't be just one or the other, internal or external. Mindfulness advocates are swinging the pendulum too far toward the individual, downplaying social and communal dimensions.

There's nothing inherently wrong with doing a three-minute breathing exercise, or taking a deep breath before sending a difficult email. However, I think we can aim higher. These kinds of individualistic techniques don't allow us to realize the full potential of mindfulness.

Dr. Purser's book, McMindfulness: How Mindfulness Became the New Capitalist Spirituality

Beyond the new capitalist spirituality

Alex: I'm beginning to see why in your book, you call modern mindfulness the "new capitalist spirituality." Capitalism incentivizes always pushing the limits. If people become more capable of coping with stress, companies have a profit motive to push them even further, making workplaces even more stressful.

Dr. Purser: Absolutely. The fact that mindfulness has been so warmly received by the marketplace should give us pause for exactly that reason.

This ties into the trend of conscious capitalism and the idea that capitalism and spirituality can be a win-win. Hedonic happiness—the focus on wanting to make myself just a little bit happier—reinforces consumer capitalism. That's why I call mindfulness the latest capitalist spirituality; it has become part of the wellness industry, the happiness industry, and the positive psychology industry.

Capitalist spirituality works as a contemporary form of the Protestant work ethic. The puritan mindset is that you worked hard under difficult conditions because it increased your chances of getting into heaven. Mindfulness is similar, in that it's a salve against oppressive working conditions that we put on in exchange for the promise of career success.

Remember that modern mindfulness was started by socio-economic elites, especially in the tech sector. Individuals with wealth, power and media savvy portray themselves as spiritual entrepreneurs that can bend the practice of mindfulness to serve corporate interests. That's why I see it as a pseudo-corporate spirituality—a virtuous signaling of "look how hip and cool and caring we are because we give our employees mindfulness programs."

Alex: For those who still believe in the virtues of mindfulness but are wary of the many downfalls you've put forward, how would you recommend they practice mindfulness? What should be kept in mind when doing these techniques?

Dr. Purser: I have a longer-term vision of radical mindfulness that would stimulate a new vision of reality, help us come into contact with one another and have a sense of how interdependent we are.

Sitting in silence or just listening to a meditation app is no longer cutting it. We need to move from highly individualistic practices to more social practices, with critical dialogue to build collective attentiveness or collective mindfulness of the structural and systemic forms of suffering in our world.

In other words, we need to ask ourselves: What is mindfulness really for? Who does it benefit? What are we mindful of? We should stop using mindfulness as a tool to help people adjust to modern circumstances and institutions that are exploitative or fraught with inequality.

We also need to stop privileging silence. Many people have the idea that mindfulness is a silent practice, but there are dialogues. Even in clinical therapeutic mindfulness, people talk about their experience. You can open that conversation up to critical inquiry! When a participant says, "You know, I was really angry," instead of telling them to just go back to watching their breath, ask them "What were you angry about? And why?" Let's encourage people to gain insight into their feelings as they arise, in the social and economic context of their lives.

This comes back to a famous point made by C. Wright Mills in The Sociological Imagination . We have to help people connect the dots between their personal troubles and public issues. Not all woes can be reduced to psychology.

I call this way of thinking "civic mindfulness." When people practice civic mindfulness they're gaining insight into their personal troubles, worries, anxieties, insecurities, and how those are linked to social and political conditions. Sharing those insights in a communal context builds bonds of solidarity. It goes beyond just individualistic stress reduction or behavioral management. Civic mindfulness reorients the practices away from purely instrumental ends, and opens the possibility to be critical of society, forging a commitment to social justice and more resistant communities.

There are principles, deep practices in Buddhism that can be leveraged in this direction. But we have to invent our own socially engaged form of mindfulness that goes beyond the therapeutic. Mindfulness has radical political potential, but it hasn't been tapped yet.

Written by Alex Steullet and edited with the help of Dan Takahashi and Toko Suzuki. Photograph and book cover illustration courtesy of Ron Purser. More information at Dr. Purser's personal website.

Writer

Alex Steullet

Alex is the editor in chief of Kintopia and part of the corporate branding department at Cybozu. He holds an LLM in Human Rights Law from the University of Nottingham and previously worked for the Swiss government.

Photographer

Dan Takahashi

Dan is an editor and photographer for Kintopia's Japanese twin website Cybozu-shiki. He is the most recent member to join the corporate branding department at Cybozu.

Editor

Toko Suzuki

Toko is an editor and translator for Kintopia's Japanese twin website Cybozu-shiki and a member of the corporate branding department at Cybozu. Prior to joining Cybozu, she worked as an editor for a publishing company and a consulting firm.