We Know the Business Case for Diversity, so Why Are Boards of Directors so Homogeneous?

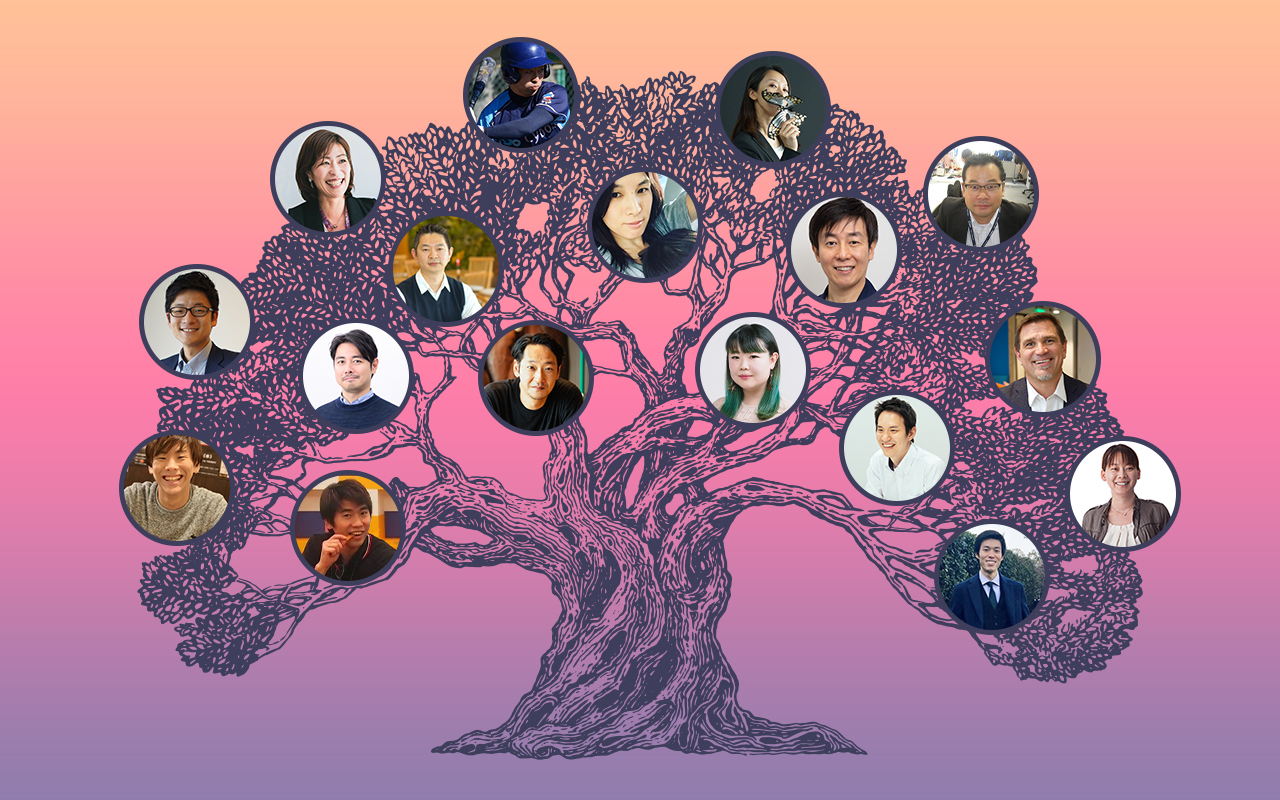

The board of directors at Cybozu

I'm now in my third year of working at the Tokyo headquarters of the leading Japanese groupware development firm Cybozu—although since February 2020 I've mostly been operating out of my apartment in the suburbs. In my time here, I've learned a thing or two about what it's like to be in the minority. We have around 500 Tokyo-based employees, and I can count the number of European colleagues I have on the fingers of one hand.

I've come to realize that when there aren't that many people you can relate to at work, diversity becomes more than a corporate buzzword.

You see whether or not diversity was taken into consideration when a new policy is implemented. You hear it in your colleagues' assumptions about what the work environment must be like for everyone. You think about it when you envision the future of your career at your company.

That's why I was so delighted to hear about Cybozu's new initiative to diversify and democratize its board of directors. It's a bold corporate governance reform project that makes sense for a globally expanding company.

The business case for diversity

To understand why these kinds of initiatives matter, it's important to take a step back and understand why I advocate for diversity in the first place. There is absolutely a selfish element: If my workplace is friendlier to diversity, I feel like I have a better chance of having my opinions heard, being selected for important projects, and perhaps even getting promoted. I don't think there's anything wrong with advocating in your own self interest, as long as it leads in the direction of more equitable treatment.

There is however a much broader business case, which has been pushing some of the world's largest companies to be more proactive than ever about diversity.

Part of that trend toward diversification stems from companies being more socially conscious. The benefits to society are manifold: Decision makers are becoming more diverse, which in turn means their decisions better reflect the diverse needs of their communities. While our world still writhes under the weight of injustice, we're at least making small steps toward equalizing opportunities for everyone.

There's no denying that some business leaders genuinely care about both doing well and doing good.

Yet in my view, it isn't these moral considerations that are driving most businesses to diversify. While morals may at best be in the same car, the driver's seat is occupied by the usual suspect: profit. For any enterprise, no matter how progressive, profitability is the key to survival and long-term well-being.

The fact that diversity is getting so much attention is a sign that its link to profitability is clear to the point of being undeniable. Research shows that diversity has real downsides—like making communication slower and more complex—but much bigger upsides in fostering creativity, better decision making, and long-term growth. On top of that, seeking out diversity means access to a broader talent pool, new ideas, and new markets.

With such an overwhelming business case, it's only natural for companies to follow suit, right? If only it were that simple.

What happened to the board?

While teams have become more diverse and we see more women and people from minority backgrounds in positions of power, your average board of directors still looks like Sunday pre-golf brunch at an upscale country club. There's been some progress—for example with new legislation in California mandating more diversity in the boardroom—but even there, top corporate decisions are being made by people who are all overwhelmingly of a similar age, with a similar educational and socio-economic background.

Now here you may stop me and say, "Well of course! Don't we want to be governed by successful and experienced individuals?" To which I would reply, "How did you manage to interrupt me writing this article?" and more importantly, "No, we want diverse governance!"

If you have to choose one leader, sure, go for someone with experience and a stellar track record. Three leaders, probably three different flavors of success. But if you're choosing a dozen decision-makers, that's when you want them to start looking like the company they're representing. Otherwise you risk fostering groupthink, overly prudent decision-making, and bureaucratic inertia—challenges that have been the downfall of many once-innovative organizations.

So if the business case is so obvious and companies are indeed the rational profit-driven machines my economics teacher taught me they are, why the discrepancy? What's holding companies back?

For Cybozu, the reason was mostly that diversity wasn't on the radar. That is, until recently, when a Cybozu initiative led to a whole new conversation about the importance of diverse representation.

For the stakeholders, by the stakeholders

Since Cybozu became a public company over twenty years ago, the board of directors had always comprised three wise, now middle-aged Japanese gentlemen. They came from a variety of backgrounds and did a fairly good job of steering the ship, making Cybozu the most successful groupware provider in the country.

Nevertheless, one of the board members was dissatisfied. Vice president Osamu Yamada began asking himself, "Do we really need this much authority shared between the three of us? What if something happens to us; will the next generation have the know-how to take over?"

Cybozu prides itself on being an open information company. With the exception of sensitive personal or proprietary information, every department posts an open record of its conversations and deliberations on the company's groupware platform, Kintone.

And I mean all conversations—from the weekend plans of our in-house video game club to the detailed minutes of our executive board meetings.

The logic behind the policy of openness is that people know best how to do their own jobs. In more traditional structures, hardworking employees who put their career ahead of anything else get promoted, gain authority, and direct other lower-level employees in pursuit of the executives' vision. In order to maintain that authority, managers control the flow of information, sharing only on a need-to-know basis.

At Cybozu, people still get promoted on their individual merits, but employees are responsible for directing themselves in line with the company's vision. Everyone has access to the same information, and managers are only responsible for approving certain sensitive processes—mainly salary and budgetary matters—and supporting employees in times of need.

The benefit of this open system is that it allows employees more leeway in determining the workstyle that suits them best. It offers flexibility for employees facing external constraints—like working parents and persons caring for an elderly relative—to tell their manager how they want to work, rather than the other way around. It gives people room to find their own unique way of bringing value to the company.

Except for the board of directors. That was three wise men meeting behind closed doors. The structure wasn't in line with Cybozu's corporate vision, so it had to be changed.

After some discussion, it was decided that if all information was to be open and all employees within Cybozu could be trusted, there was no reason to limit board membership. The benefits of decentralizing power far outweighed the costs.

The board became open to everyone.

A board reimagined

Since the board structure was changing, it was only natural that the functioning of the board needed to change as well.

Salary-wise, there would be no special treatment for board members. The general policy at Cybozu applies, which is that for anyone to get a raise, they first have to demonstrate they deserve it by bringing value to the company. In practice, none of the board members would get a raise just for being on the board. Removing quick financial incentives means that board members would be chosen based on their love of the company and its values, rather than their love of all the things money can buy.

Accountability-wise, all discussions among board members would be published and made available to the entire company. It's surprising how in this day and age, so many corporate leaders believe their strategy decisions deserve the same level of hushed secrecy as cardinals deliberating over who should be the next Pope. The gold standard of governance is full transparency about who said what, when, and in what context. It's what we dream about for our governments when they make important legislative decisions. Why wouldn't we expect the same of our employers?

With a common sense approach in line with the company's vision and mission, the scene was set. As Cybozu rolled into its fiscal year 2021, the details of how the board would be restructured were shared with the entire company.

All that was left was to call for candidates.

Answering the call of duty

After a generation of traditional corporate governance, the board of directors at Cybozu changed swiftly and dramatically. There were 16 applicants, all of whom were accepted. Those 16 candidates plus the CEO means the board skyrocketed from three to now 17 members.

The youngest is still in his early 20s, a new hire who only joined Cybozu a few months before the call. Another is in her mid 20s, hired straight out of university a few years ago.

Two members are based at Cybozu's US branch, and one doesn't speak Japanese. As a result, board meetings now have to have English translation and interpretation, which means an English-language record that will benefit all non-Japanese employees worldwide.

Five of the seventeen board members are women—which admittedly is lower than the overall ratio of female employees within the company (over 40%), let alone Japanese society. Nevertheless, in one fell swoop it made Cybozu the company with the most female board of director members among all top-tier companies listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

By focusing on openness and good governance, Cybozu naturally diversified. It finally had a board of directors that was starting to look more like the company as a whole.

An honest conversation about diversity

Having a more diverse board of directors doesn't mean that Cybozu has figured out diversity. It worries me that diversity was more a byproduct than the motivation behind this initiative.

I was also troubled to hear reactions from certain colleagues who believe that because everyone is a little bit different, a handful of middle-aged Japanese men can govern just as well as a more diverse group of leaders. This is what's known as the "diversity of thought" argument, and is often used to draw focus away from structural issues. As the company grows, there's a lot to be done to create an environment that's welcoming to people of all cultures and backgrounds.

Speaking and sharing controversial views with a more powerful majority is hard. When I was working in the majority in my home country, embracing minorities was theoretical. It was something I believed in, but had never experienced.

Now I'm starting to understand a bit better how it feels when none of your bosses or leaders look like you. When nobody shares your history or your culture. When the corporate values that determine your salary and promotions are different from the values you were raised to believe in. And still, with who I am, where I was born and educated, I know I have it easier than other colleagues of mine.

While this board of directors initiative doesn't address those deeper concerns, it's still encouraging. It demonstrates a willingness among top management to open up the conversation, decentralize authority and give everyone more control over their professional lives—including those who would typically be marginalized in a more traditional corporate structure.

It also gives stakeholders who would normally be encouraged to focus on a limited set of tasks an incentive to take a much broader view of the organization's activities. In the first meetings of the new board, younger members in particular shared how delighted they were to be given a comprehensive overview of the company's performance.

At Cybozu, one of our corporate values is to openly voice our opinions and engage in honest, transparent debate (in accordance with the Japanese teamwork principle of koumeiseidai, 公明正大). That corporate principle is what allows me to write articles like this one, providing my unfiltered opinion about our company's transition onto the global stage.

In pursuit of good governance, Cybozu took a step in the direction of empowering a variety of perspectives and life experiences. While diversity wasn't the deciding factor this time, hopefully by using koumeiseidai to demonstrate the power and value of diverse voices, we can make it the deciding factor next time.

I'll keep doing my part to make that happen, hopefully with the support of our 16 new board of director members.

Article by Alex Steullet. Edited by Ade Lee and Mina Samejima. Visual by Dan Takahashi.

Writer

Alex Steullet

Alex is the editor in chief of Kintopia and part of the corporate branding department at Cybozu. He holds an LLM in Human Rights Law from the University of Nottingham and previously worked for the Swiss government.

Photographer

Dan Takahashi

Dan is an editor and photographer for Kintopia's Japanese twin website Cybozu-shiki. He is the most recent member to join the corporate branding department at Cybozu.